Saffron, Saint of Spices, 2023-2024

Saffron, Saint of Spices, 2022-2024

The University of California, San Francisco Library Residency Project, 2021-2022

Solo Exhibition at the Triton Museum of Art, CA, 2023

Exhibition at Euphrat Museum of Art, CA, 2024

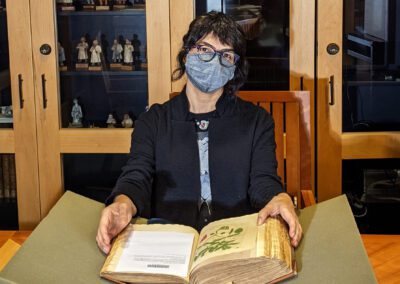

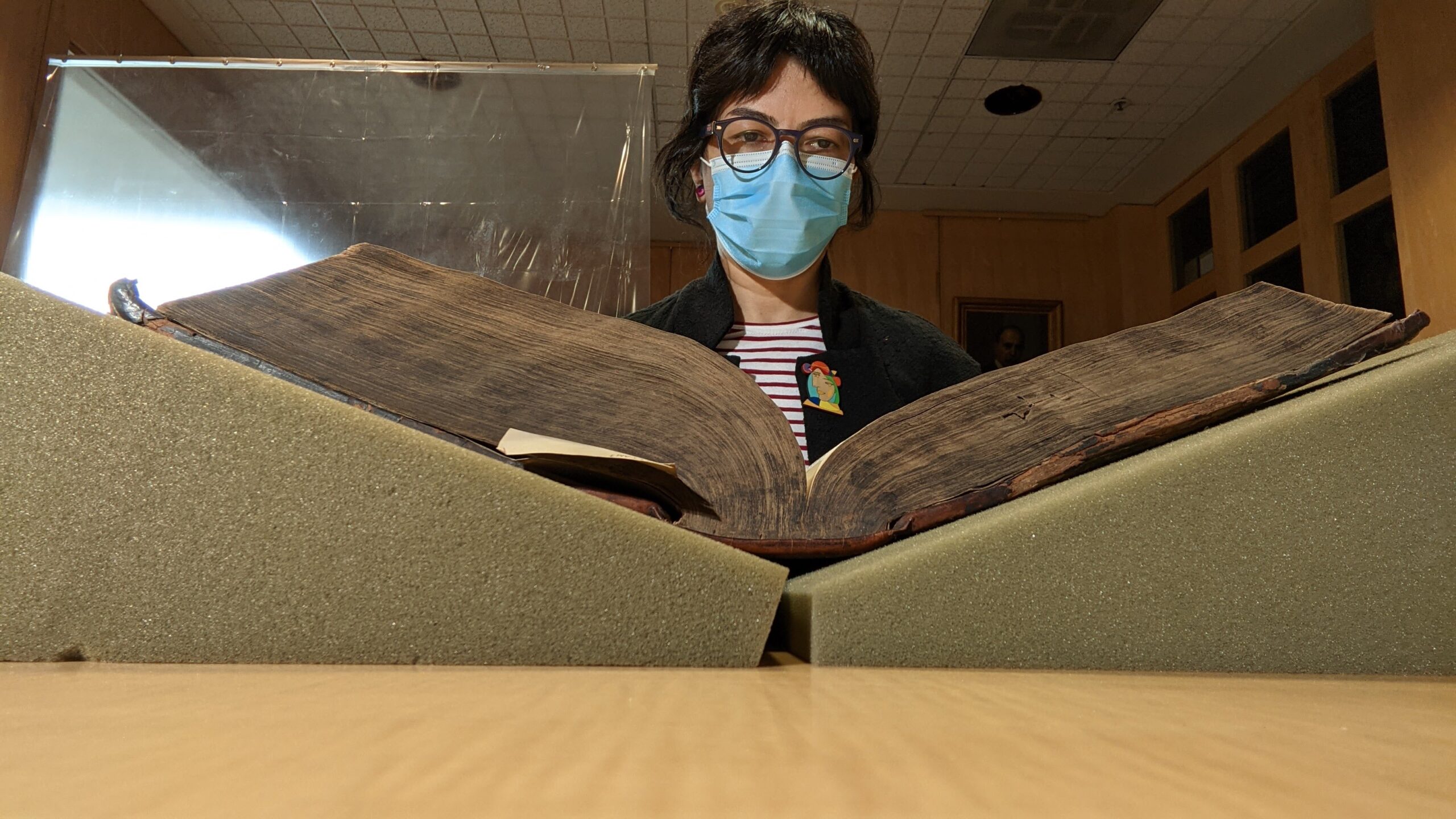

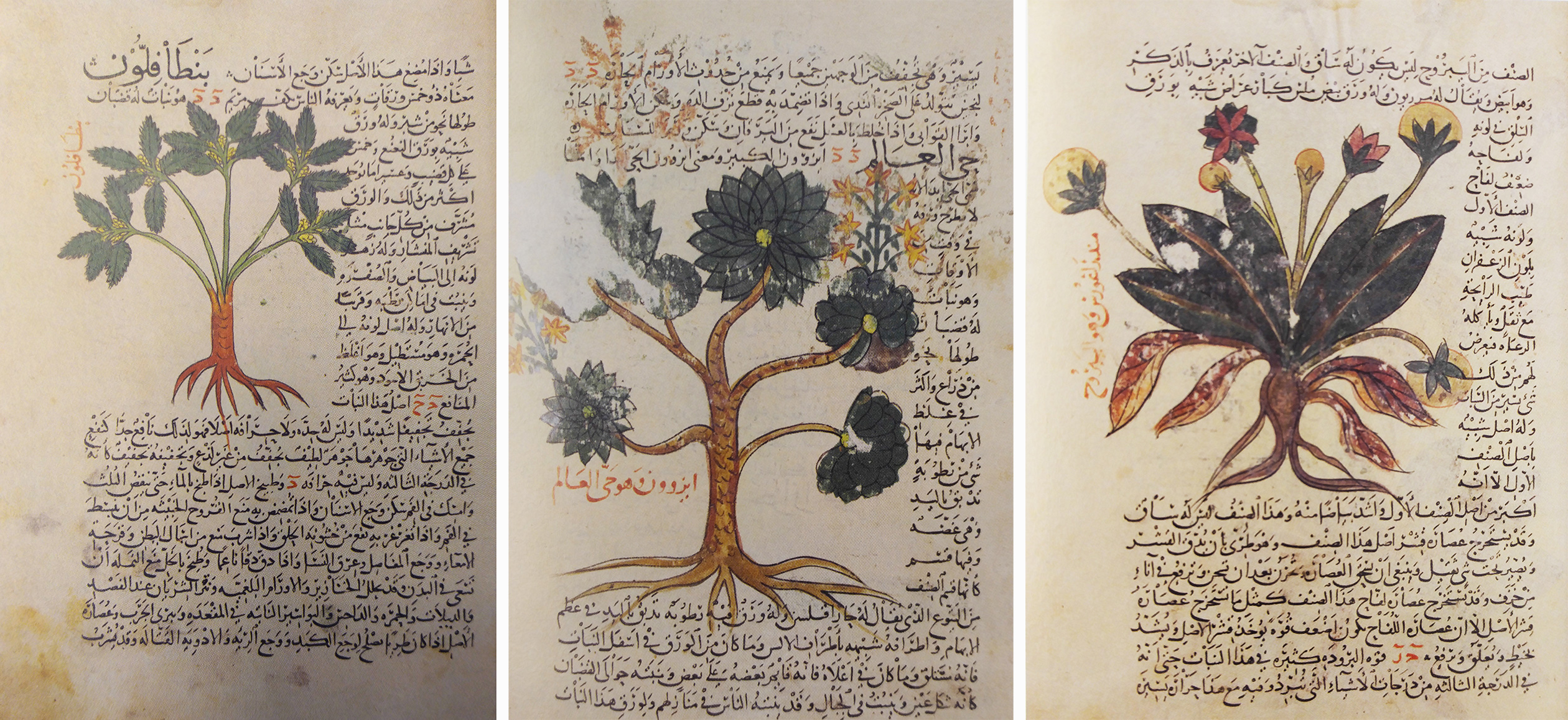

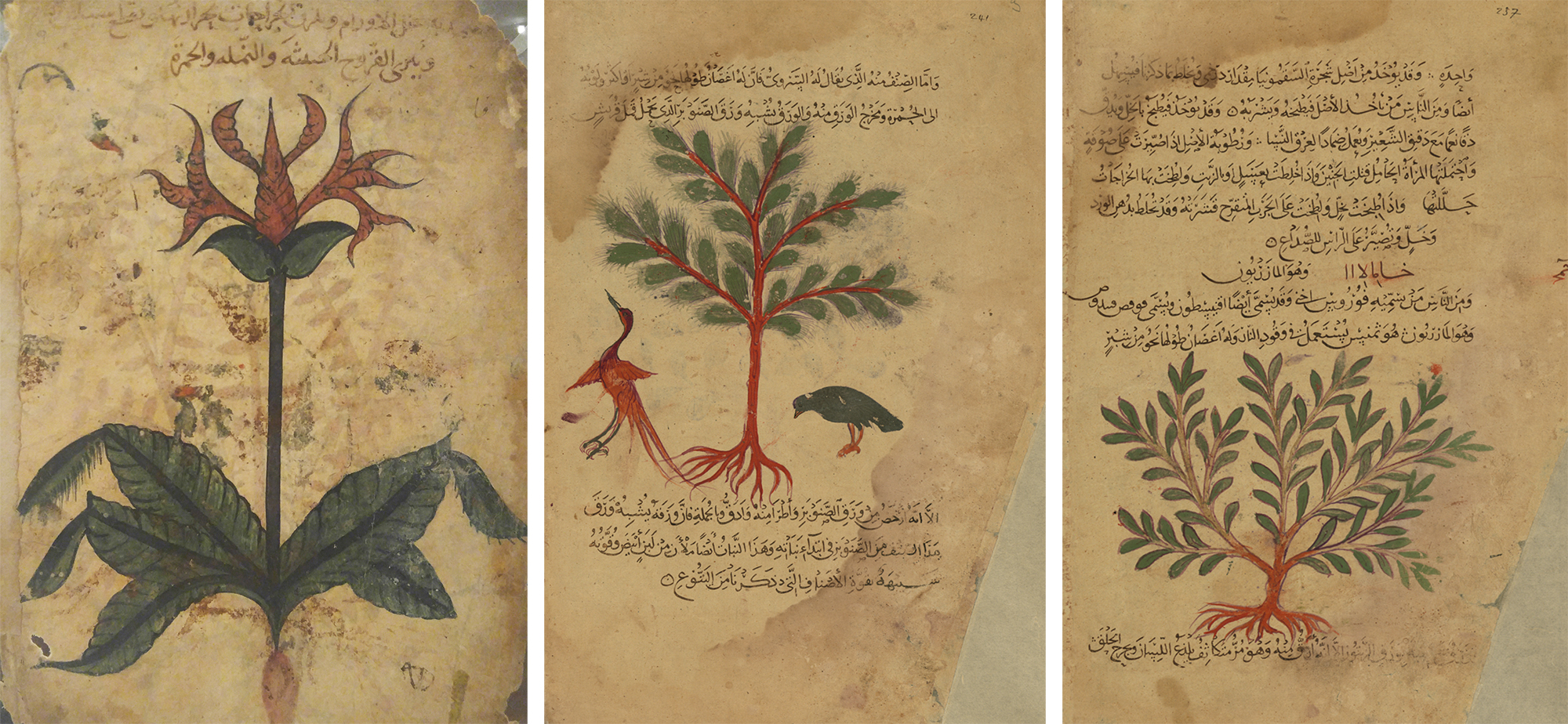

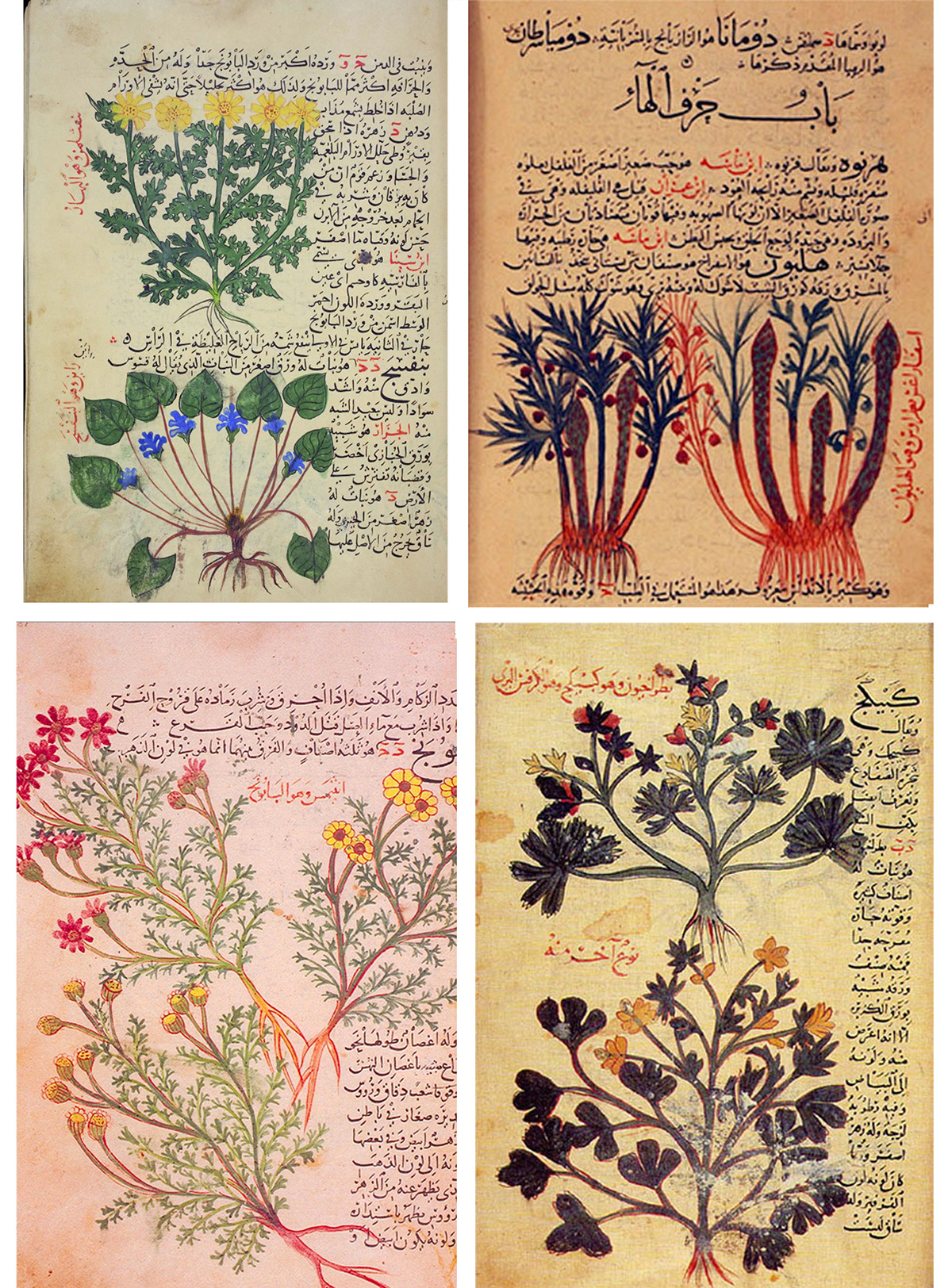

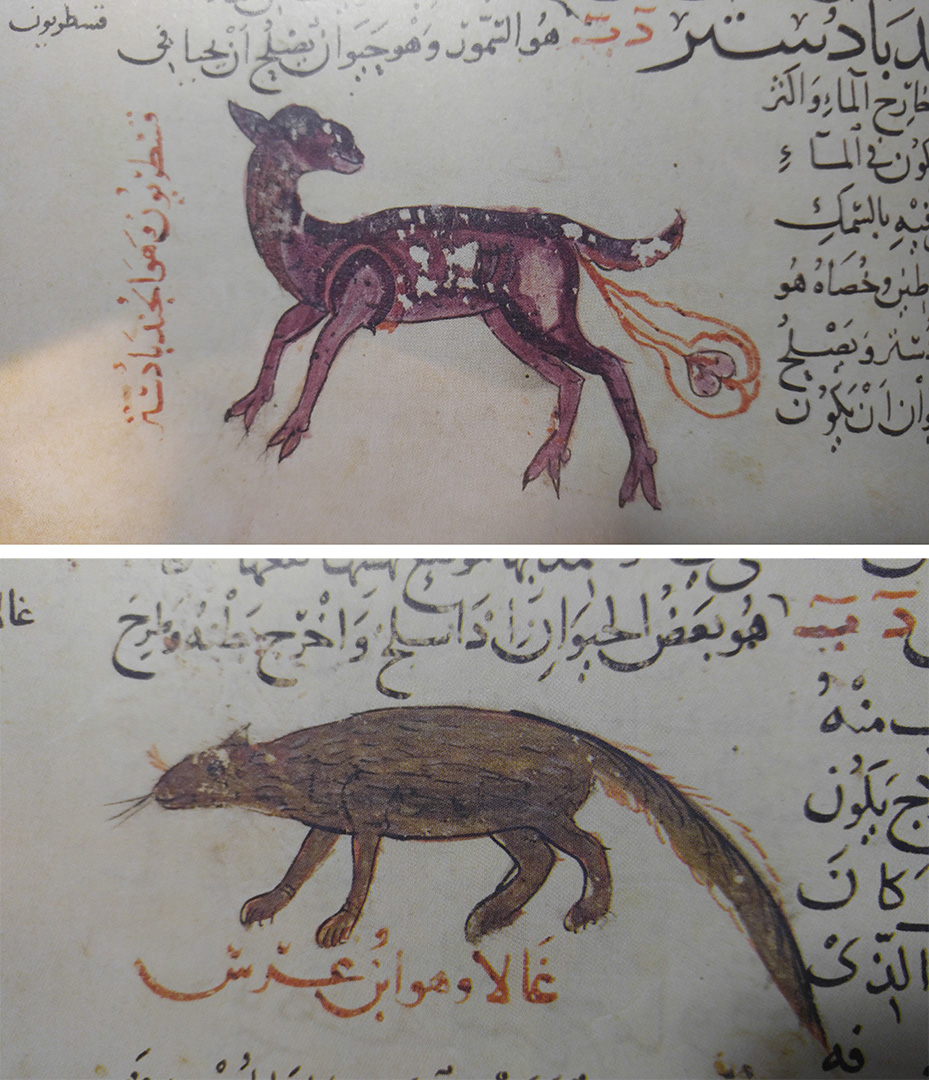

Pantea Karimi was the Artist in Residence at the University of California San Francisco Library, from July 2021 to July 2022. During her residency, Karimi explored the botanical archives, preserved in the library’s Archives and Special Collections. Among all the plant species she studied, the saffron crocus stood out because it has deep roots in Iranian culture, cuisine, and medicine.

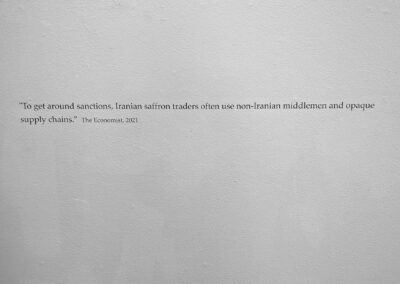

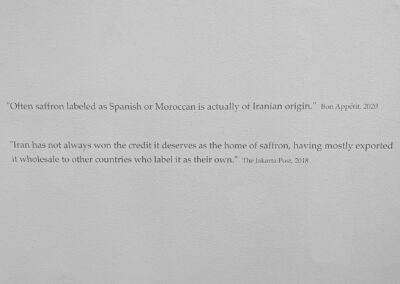

To produce 1 kilogram of saffron spice, 150,000 crocus flowers must be hand-picked. The labor-intensive harvesting process is mainly done by women in Iran, for three weeks, in the late fall each year. Iranian saffron farmers struggle due to suffocating economic sanctions, endemic drought due to global warming, and the rise of shipping and labor costs. For Karimi, the above attributes make the saffron a symbol of contemporary economic and agricultural challenges, convolved with ongoing political issues under the theocracy in Iran.

Saffron, Saint Of Spices, a solo exhibition at the Triton Museum of Art in 2023 and Euphrat Museum of Art in 2024 explores the saffron crocus from historic, medicinal, pictorial, and socio-political angles in a religious context. Through various media from bottled saffron extracts, and hand-printed marbling prints to hand-made religious objects, Karimi assigns sainthood to saffron crocus and celebrates this ancient Iranian quintessential spice, visually and conceptually.

This exhibition is funded by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and UCSF Library Award.

Videos

The Saffron 3-D sculpture and the upper section of the Triptych were manufactured at the UCSF Library Makers Lab, in collaboration with Scott Drapeau & Jenny Tai, Makers Lab Designers.

Iranian women harvesting saffron crocus in Khorasan province, where 90% of its global production grows. The delicate flower sprouts for just 10 days a year. But its harvest and distributions are now in jeopardy because Iran has been suffering from sanctions and a devastating drought for the past two decades. Video by Agence France-Presse, Nov 2018.

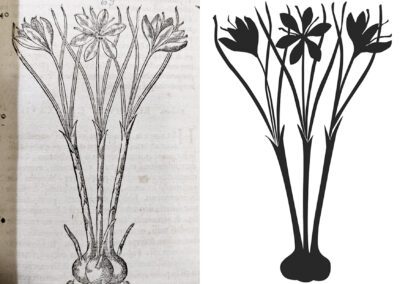

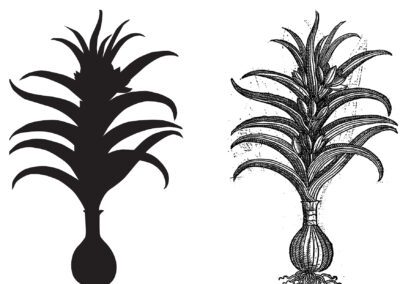

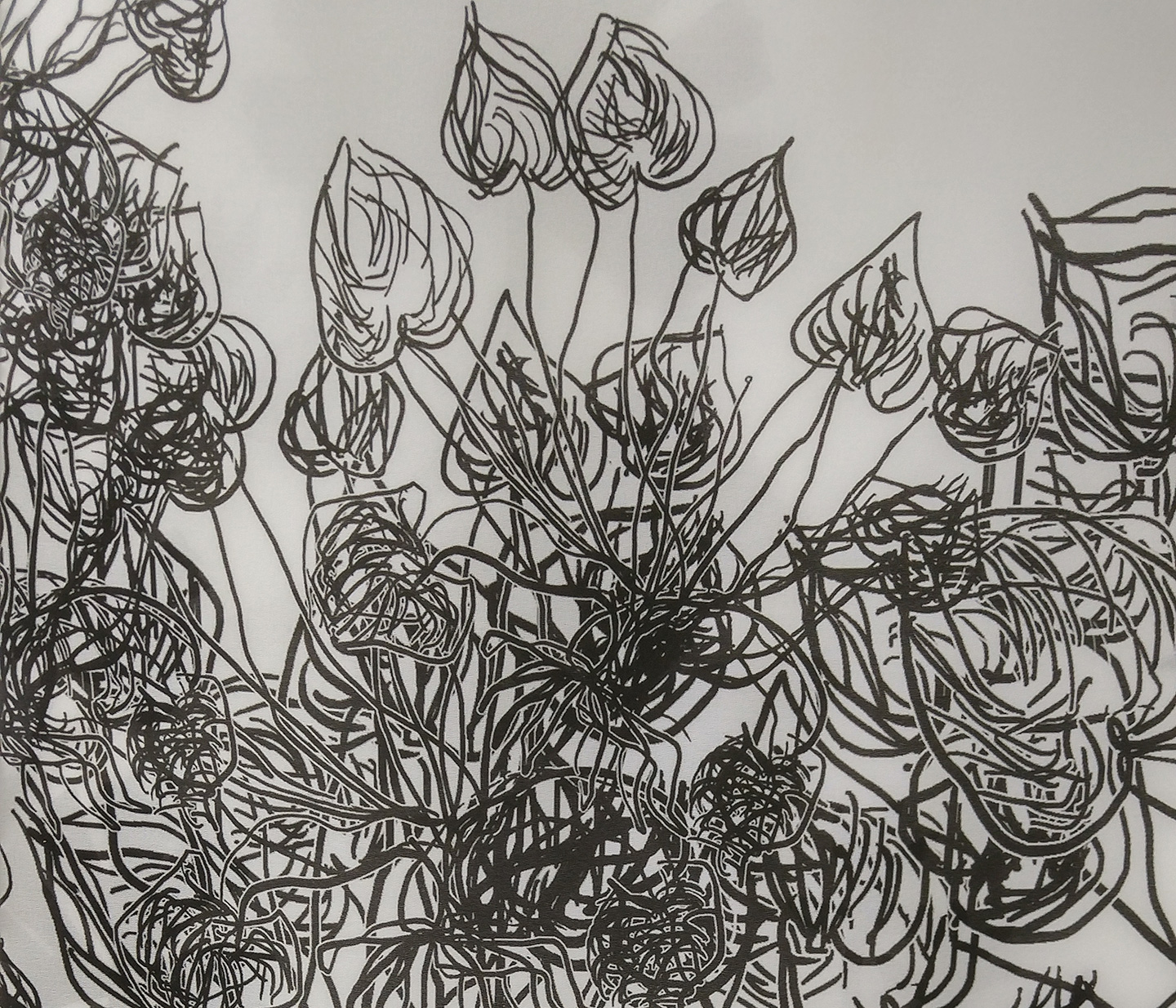

Pantea Karimi draws a saffron crocus using diluted safflower liquid on paper, 2022. Inspired by the depiction of the saffron crocus from Mattioli’s 16th c. book at the UCSF Library. Video by Pantea Karimi, March 2022.

Artworks Labels

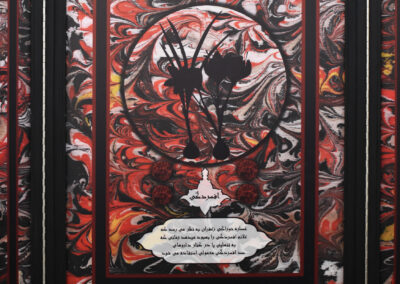

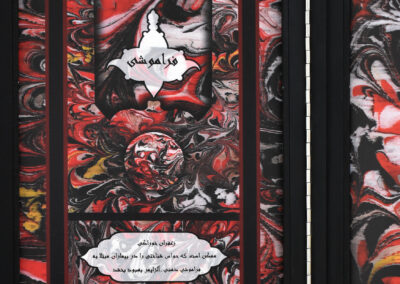

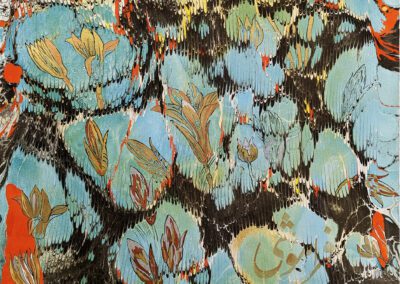

A Divine Allegory, triptych, 2022, digitized hand-printed marbling on paper, digital collage and print on wood, hand-made wood frame, hinges, and hasp, 43 x 40 x 5 in.

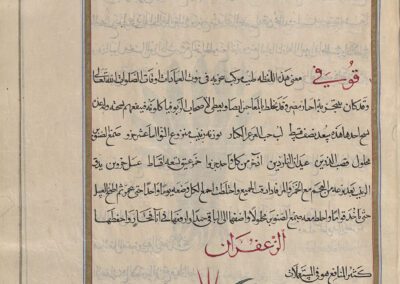

Triptych, an object of reverence since medieval times, allows for storytelling and interactivity. The triptych, A Divine Allegory, is composed after the 18th c. religious triptych, hilya-i-sherif (a noble description of the Prophet Muhammad’s moral qualities), from the Ottoman period. I replace the botanical vegetation, and the religious texts in the original triptych with saffron crocus archival images, and its healing properties in Persian. I use my digitized hand-printed marbling patterns; a plant-based printing technique from late medieval Iran. The muted color palette and black flowers reference the absence of proper attribution of saffron to Iran where 90% of worldwide saffron crocus is cultivated. The subdued hues invite the viewer to have intimate proximity to the work and mitigate visual frustration.

Translation of texts on the triptych:

Left panel: Alzheimer’s disease. Oral saffron might modestly improve cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Right panel: Anxiety. Small clinical studies suggest that oral saffron might improve anxiety.

Middle panel: Depression. The oral saffron extract seems to improve symptoms of depression when used alone or as an adjunct to conventional antidepressants.

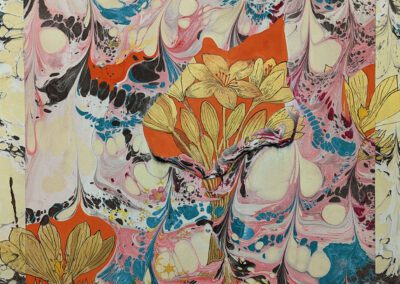

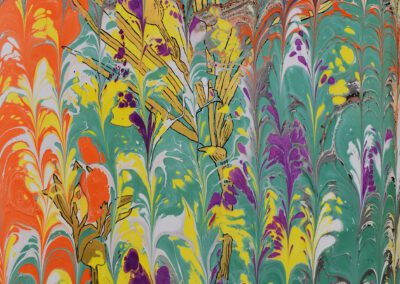

Saffron Crocus, Tradition, (Sonnatee in Persian), 2022

Saffron Crocus, Lust, (Mayleh-Jensee in Persian), 2022

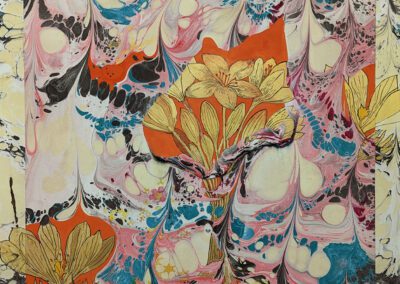

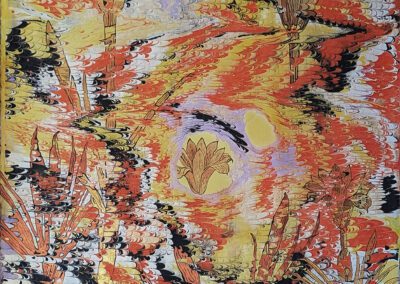

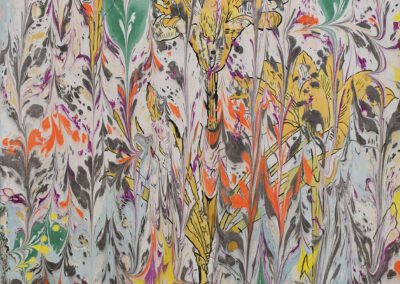

Hand-printed marbling, gold acrylic, and gouache on paper, each 36 x 24 in

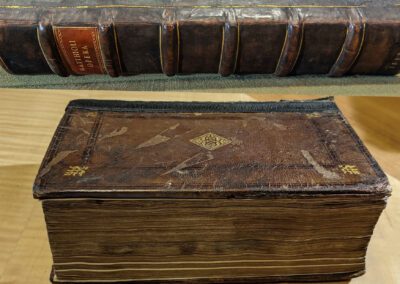

I use images of the saffron crocus, originally printed from hand-carved woodblock plates, which I extracted from the 17th and 18th c. UCSF Library’s hand-bound books. By painting saffron crocus in gold in between the patterns, I intend to highlight the exceptional nature of the flower while preserving the integrity of the original images. The marbling patterns, suggesting fragmented landscapes, incorporate my drawings and hand-written healing properties of the saffron crocus, in Persian, having both cultural and religious connotations. Marbling references those decorating papers with mottled designs that were used for manuscripts’ binding throughout the history of book-making.

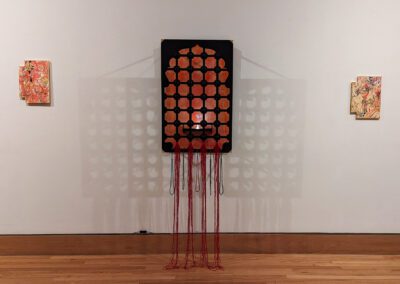

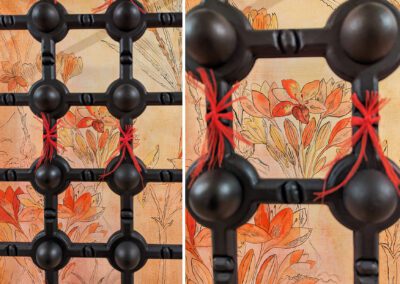

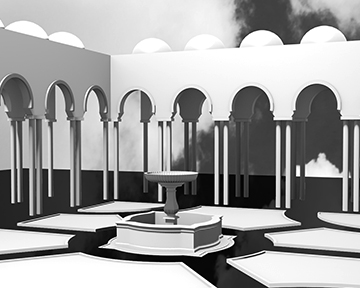

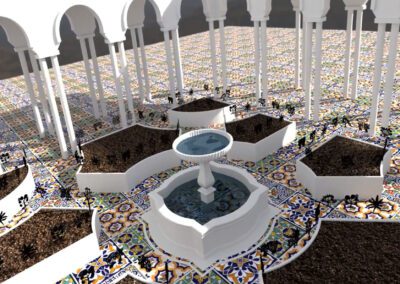

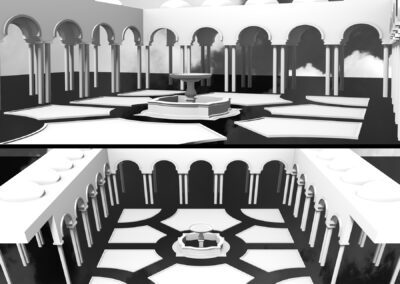

Sacred Threads i & ii, shrine-Saqqaakhanaa, 2022, Iranian style shrine-facades, watercolor on boards,

3-D saffron crocus sculpture, light, threads, prayer beads, and metal, 37.5 x 24 x 10 inches

The shrine objects are designed after the Iranian shrines and Saqqaakhanaa – the (religious) water fountain. The visitors would leave votive items such as flags or locks on the grided exterior of the Saqqaakhanaa which is often decorated with religious objects such as candles or (prayer) beads. Either inside or outside of the structure there is a fountain for drinking. The votive red threads are symbols for healing wishes and the 450 saffron threads make up the 1-gram saffron spice. The illuminated 3-D saffron crocus flower sculpture was manufactured in collaboration with the UCSF Library Makers Lab in 2022.

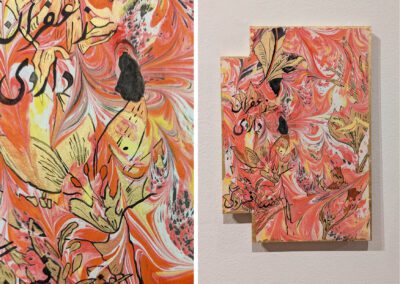

Pious Readings i, ii, iii, prayer pages, 2022, hand-printed marbling prints on paper stretched on wood panels, gold paint, watercolor, and gold leaf, each 15 x 10.5 x 1/4 inch

The layouts and designs are inspired by the late medieval Iranian prayer books’ pages that were illuminated and decorated by vegetal scrolls and vines in vibrant gold. The Persian words describe the anti-depressant saffron healing properties, replacing religious texts.

Cartographical Re-Shapes, 2022, diluted safflower on hand-made paper, wood hangers, and screws, each 27 x 21.5 inches

On hand-made papers, I use diluted safflower to draw the map of the Khorasan province, where most saffron is cultivated in Iran. I started drawing the map within defined boundaries but gradually the natural liquid spread into the rugged paper and re-shaped the map organically. The new shapes are a metaphoric reminder of water staining the rugged-dried grounds where saffron crocus grows. Safflowers are occasionally used in cooking as a cheaper substitute for saffron.

Healing Chroma, 2022, diluted saffron spice in glass bottles, cube structure, and board, 30 x 30 x30 in

Kaaba was one of the first extensive geometric objects I discovered in our religious courses at school in post-revolutionary Iran. The word means cube in Arabic and it is the most sacred Islamic site. Plato in Timaeus c.360 BC wrote about Platonic solids in which he associated each of the four classical elements -earth, air, water, and fire- with a regular solid. Earth was associated with the cube. Diluted saffron, in various chromatic concentrations in medieval-style bottles, is placed on a platform in the middle of a cube structure, representing a sacred site.