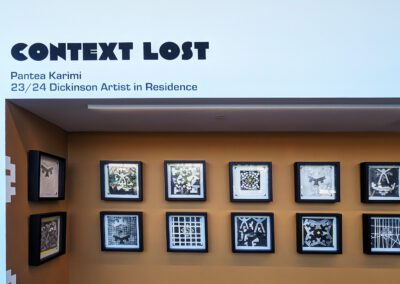

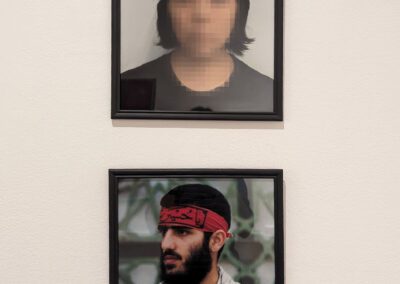

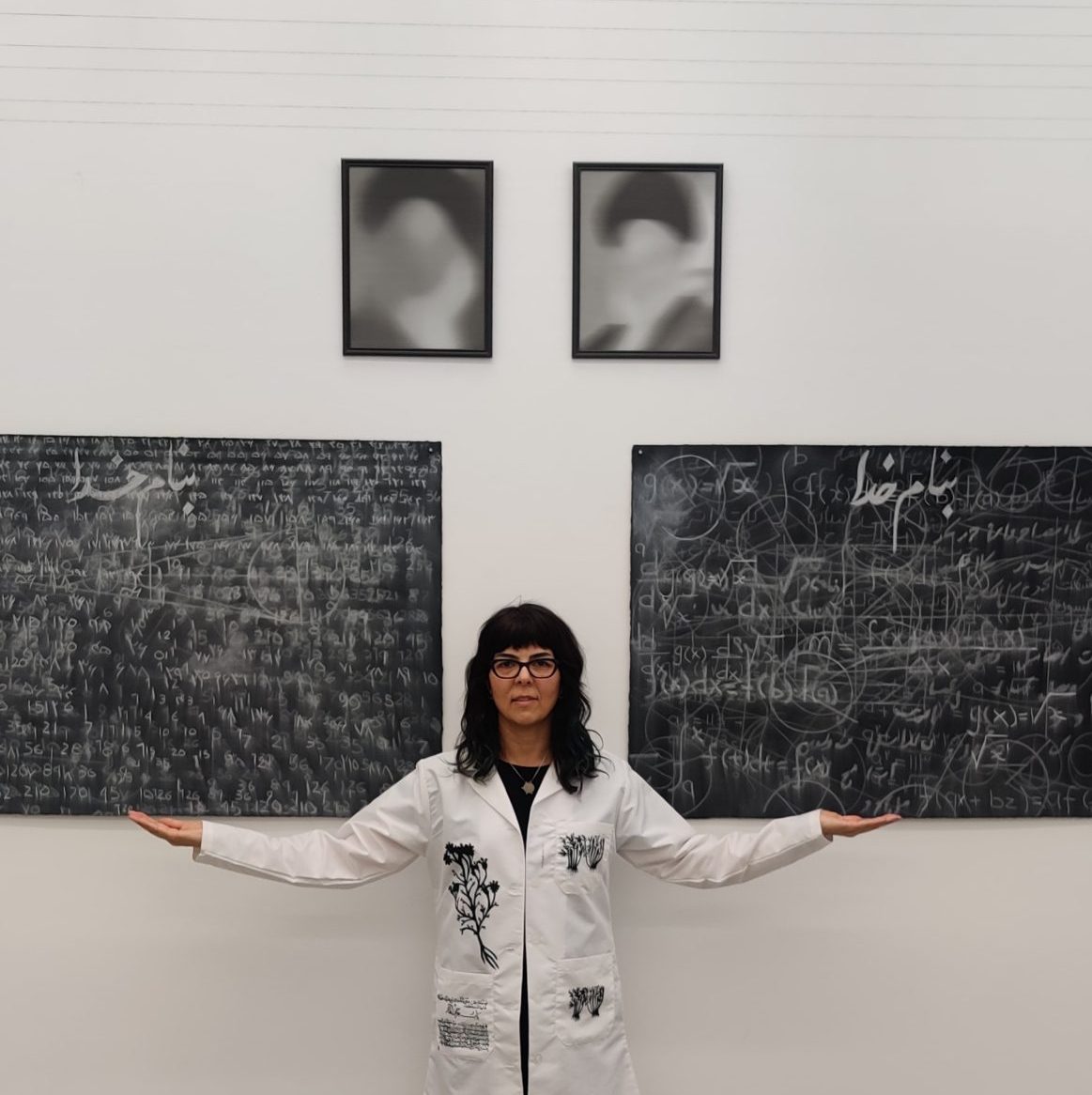

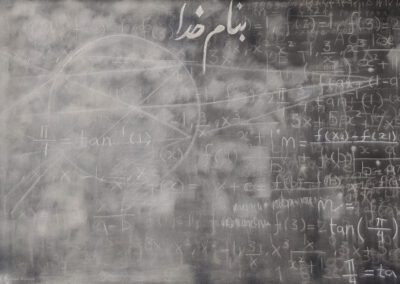

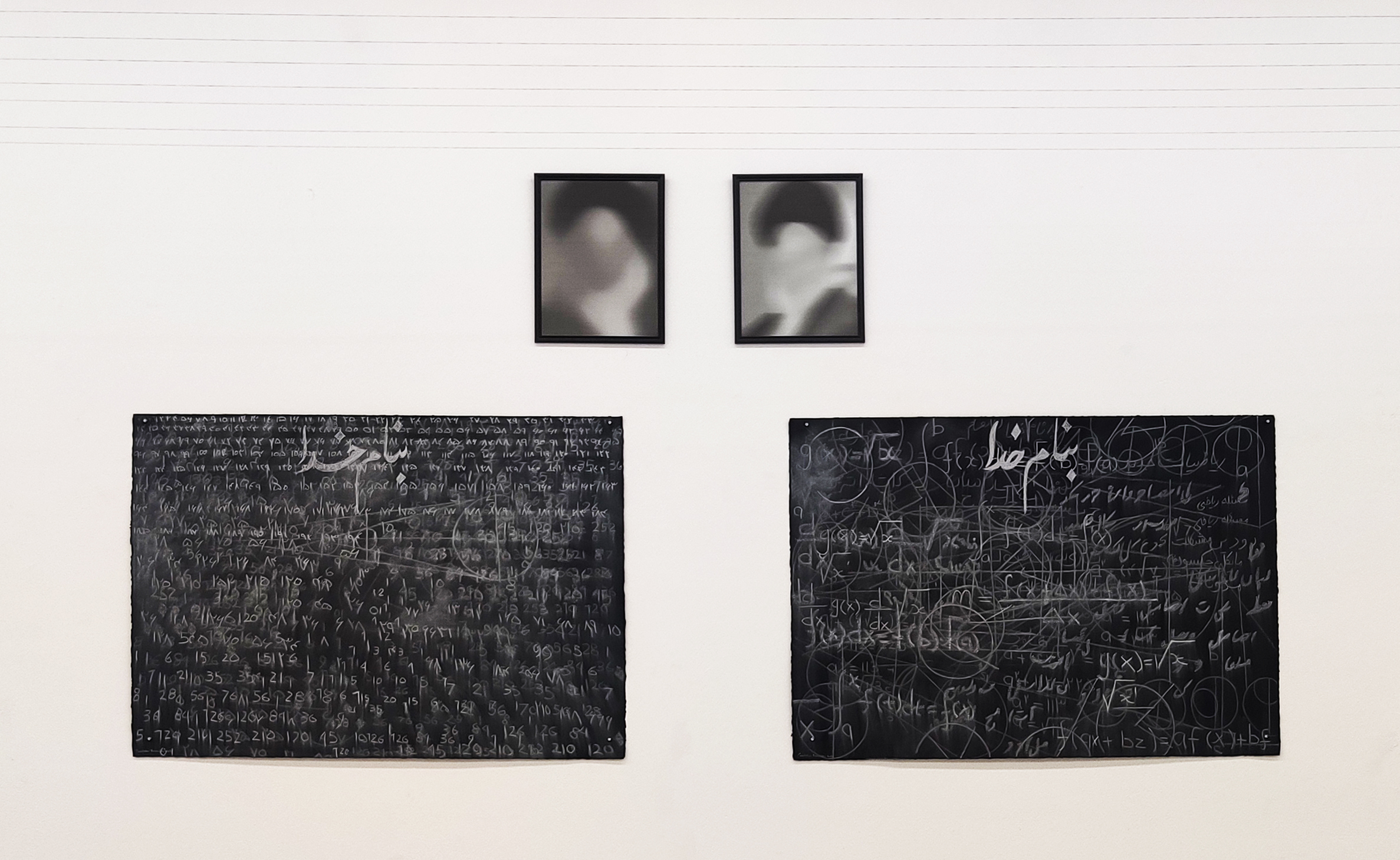

Context Lost, 2022-2024

Context Lost, 2023

Solo Exhibition, Krishna Murthi Gallery, Rothschild Performing Arts Center, San Jose, CA

2023 Dickinson Artist in Residence Project and Exhibition

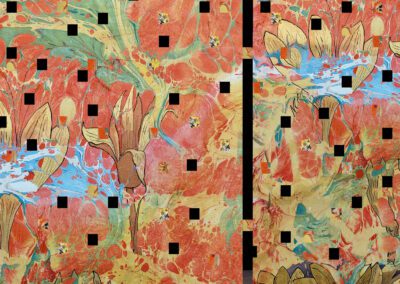

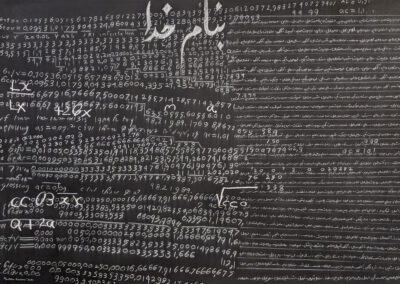

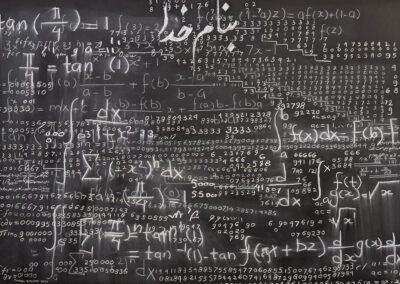

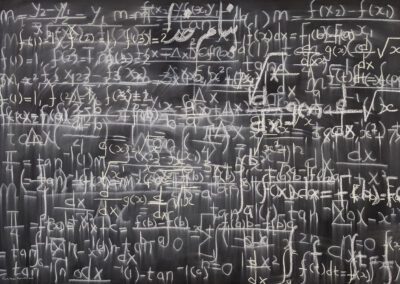

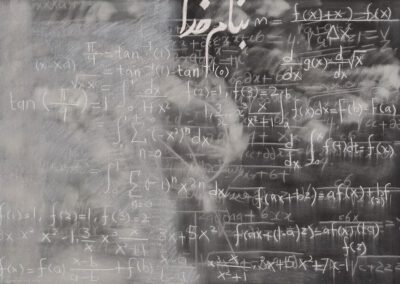

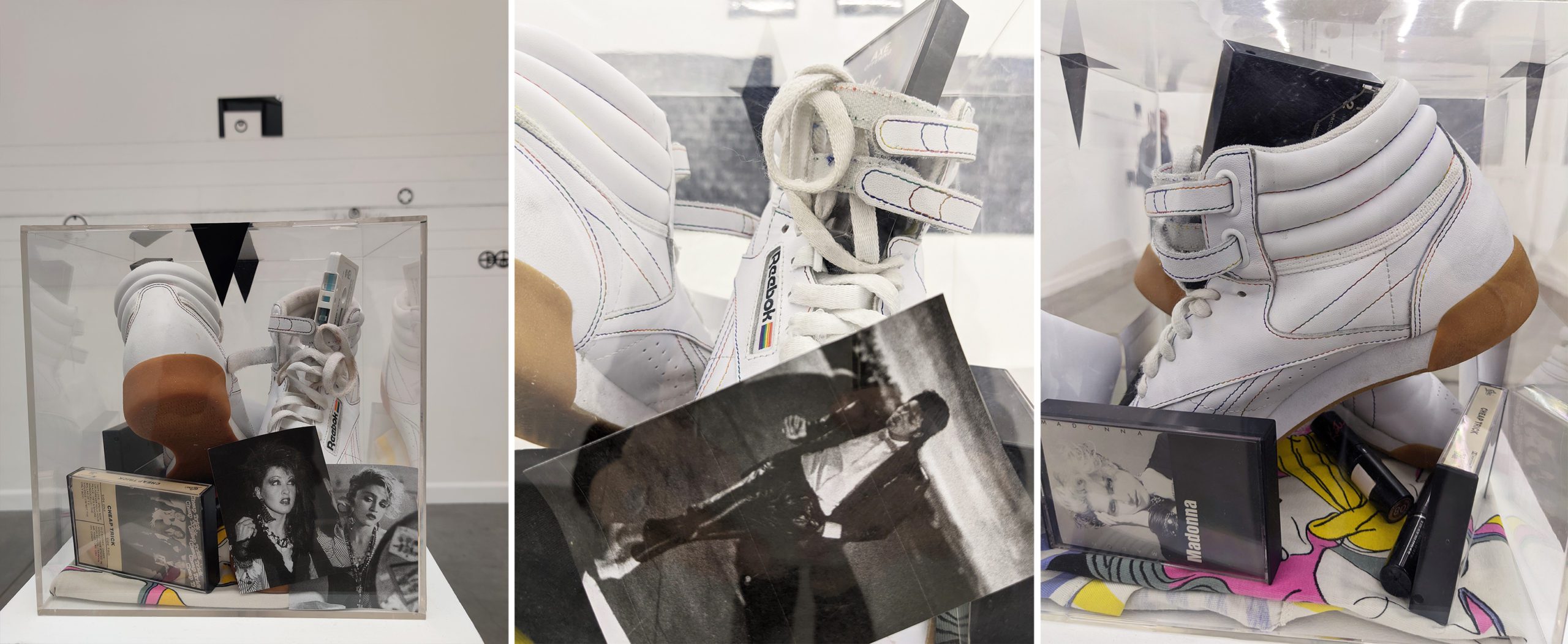

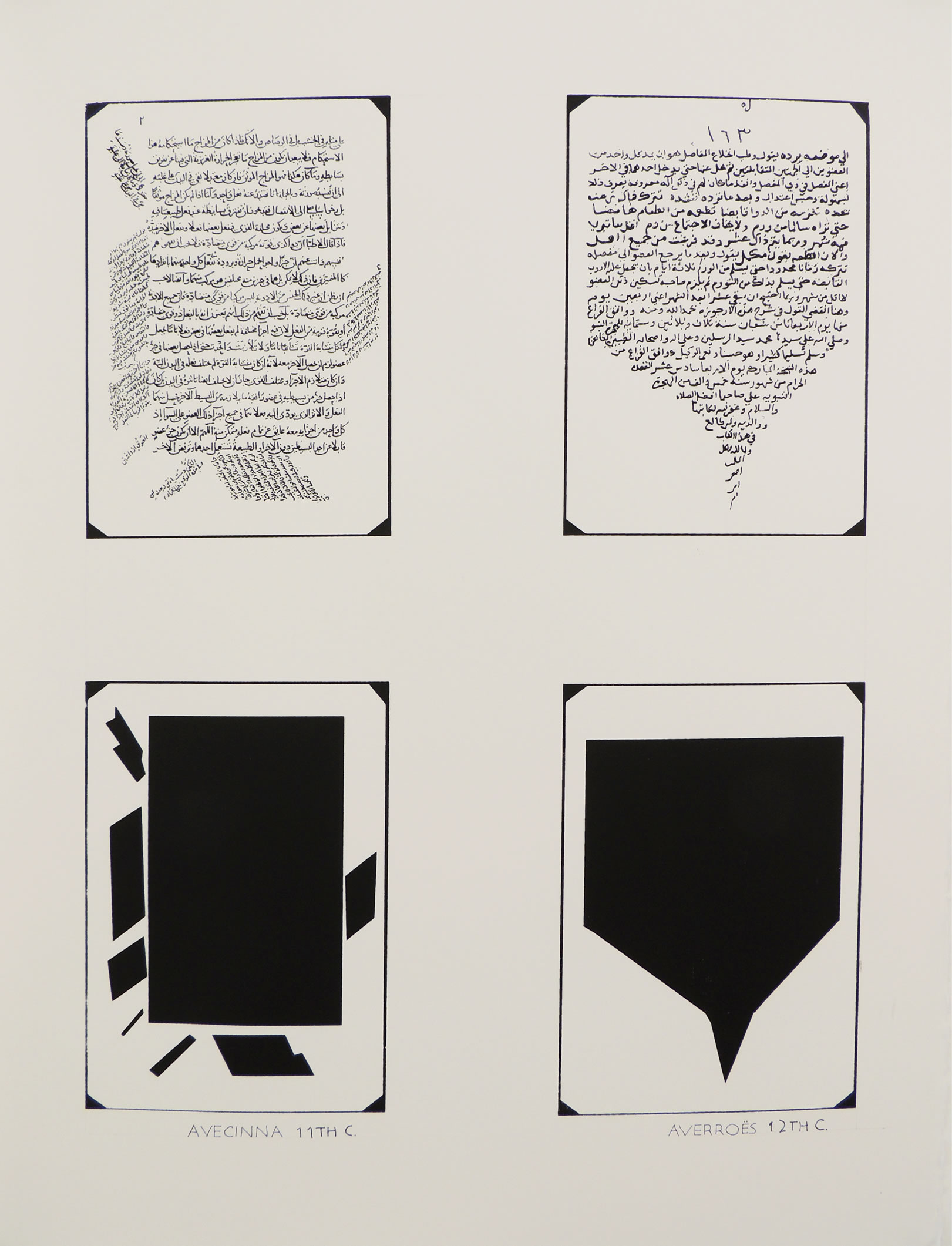

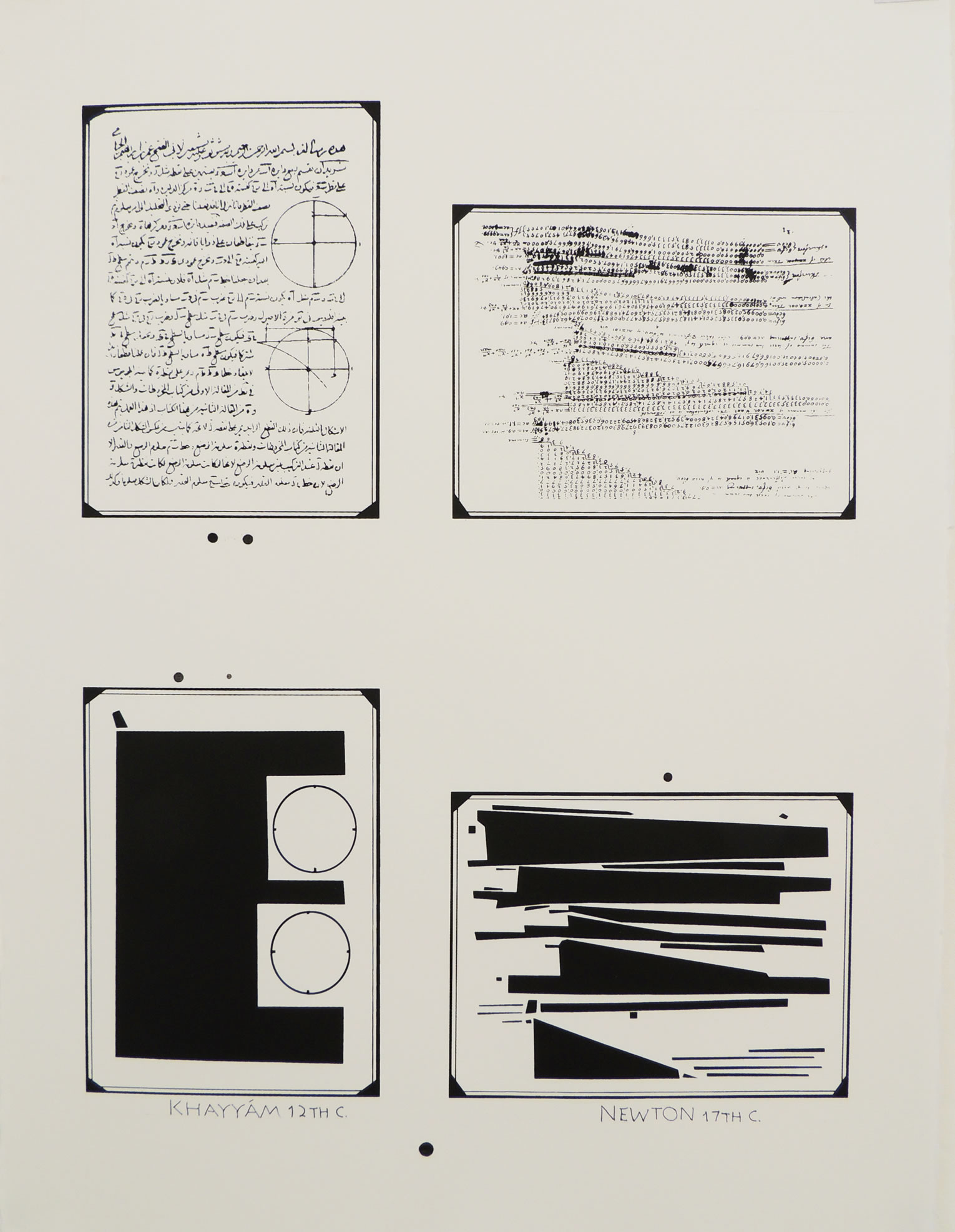

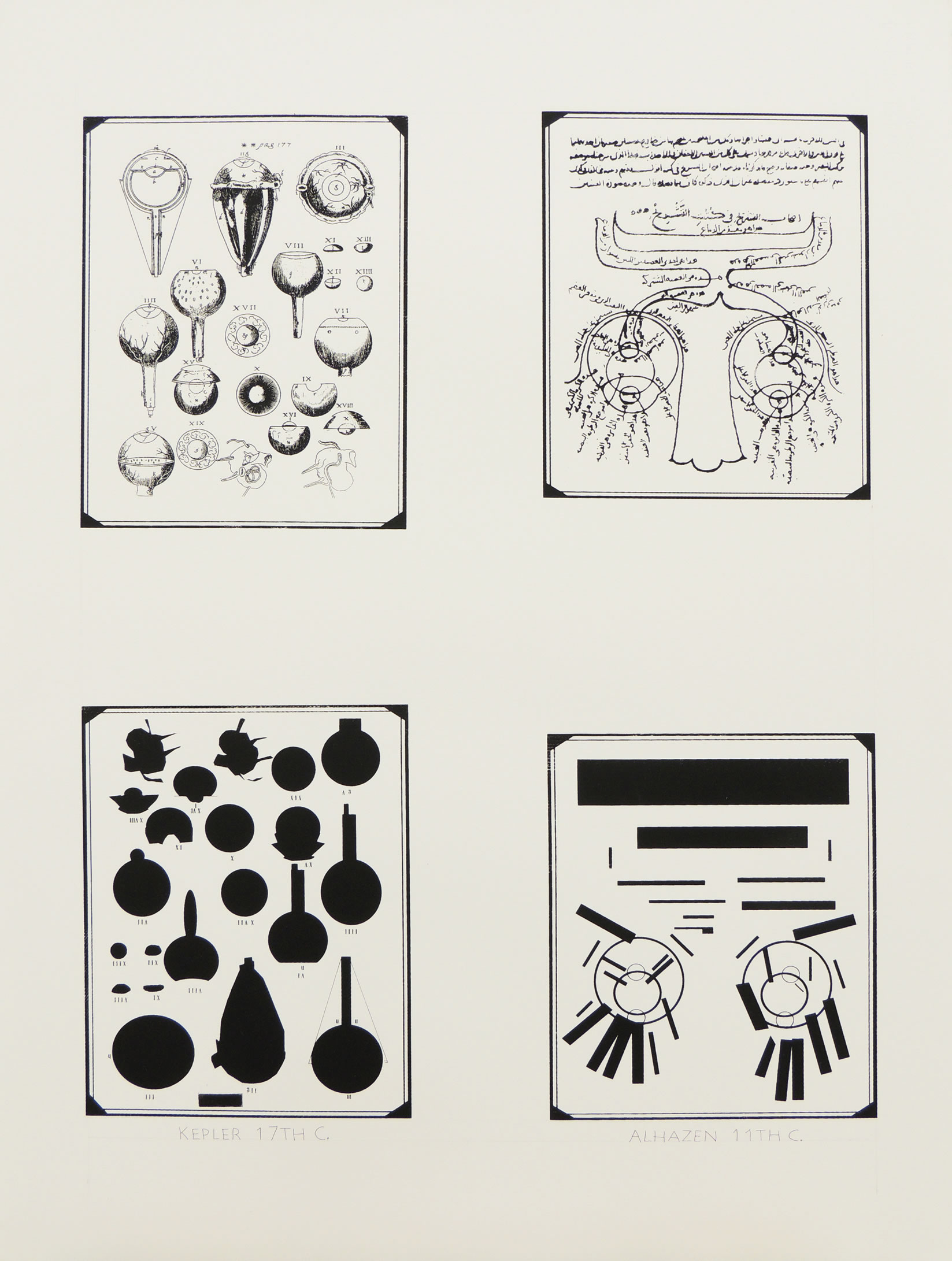

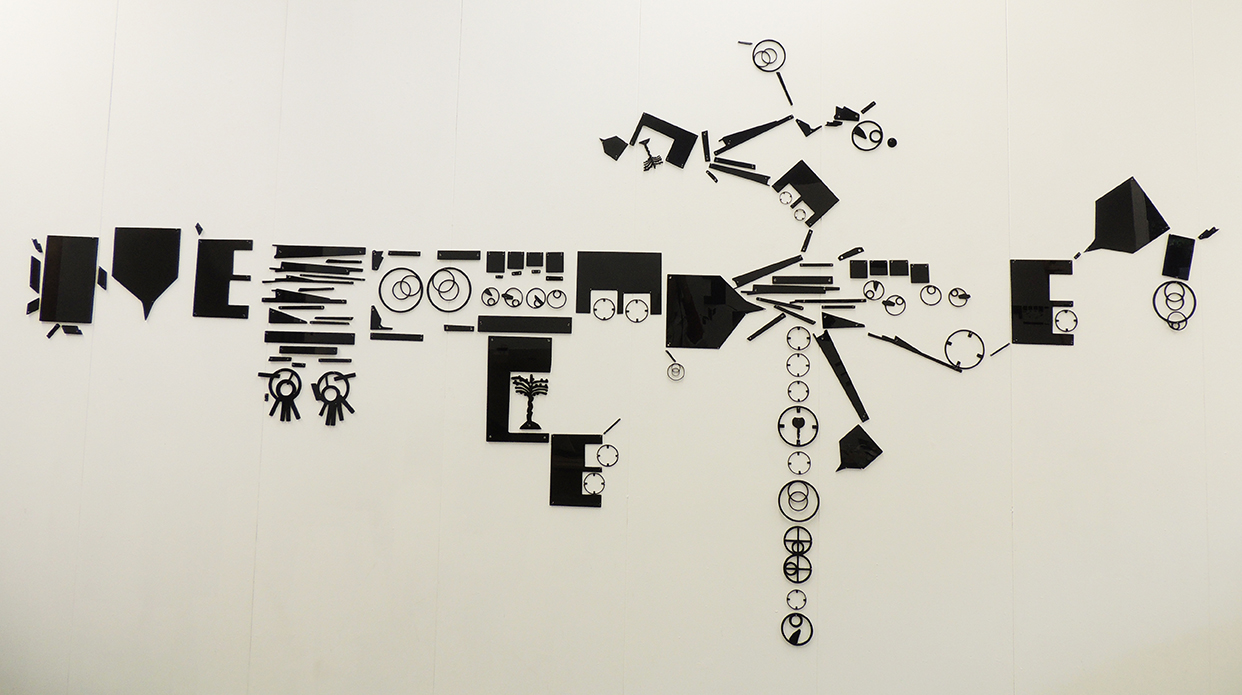

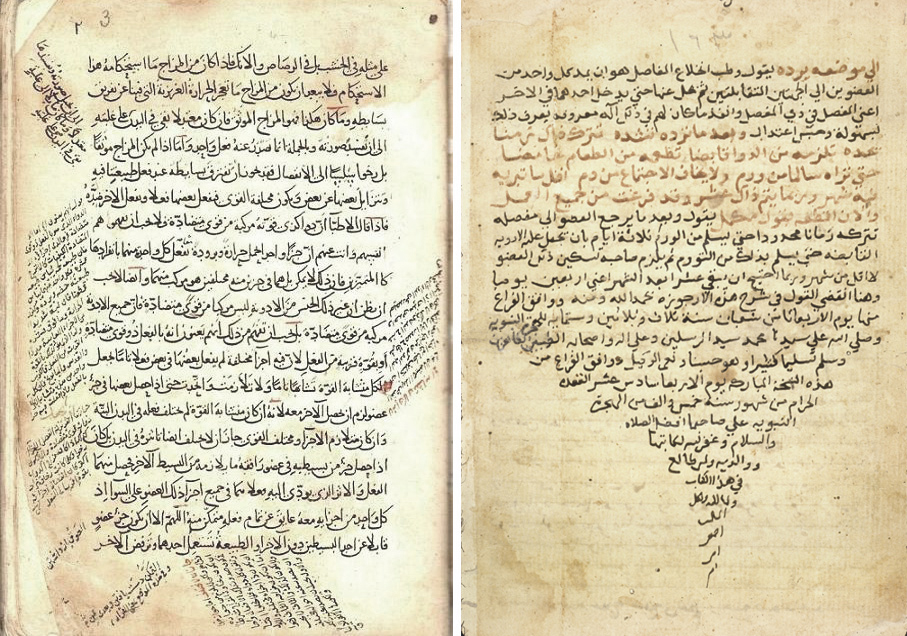

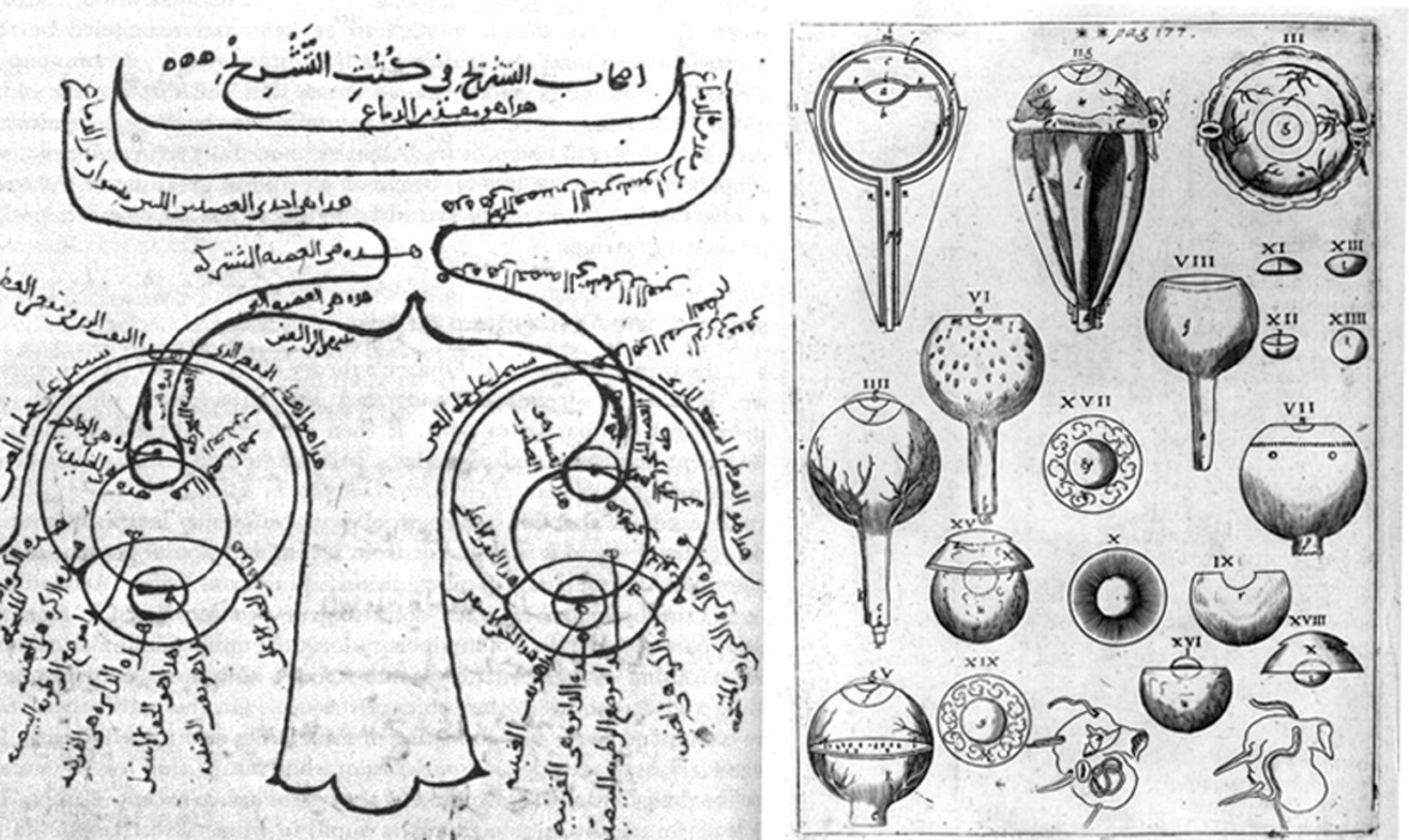

Context Lost displays existing pieces from my geometry and botanical series in which I incorporate references to my home culture, Iran. Much of Iranian customs, heritage, and values are unknown outside of the country, and geopolitical representation of Iran also serves to obscure and misinterpret it. Because of this, my works are necessarily viewed through an arbitrary syncretic and invented lens. I juxtapose traditional and contemporary art forms as commentary on the intricate interplay between culture and politics. Iran’s history includes much conflict and uncertainty. I seek to introduce and raise questions about the impact of political conflict on Iran’s deep history of scientific, artistic, and cultural achievement, thereby revealing the context that has been lost.

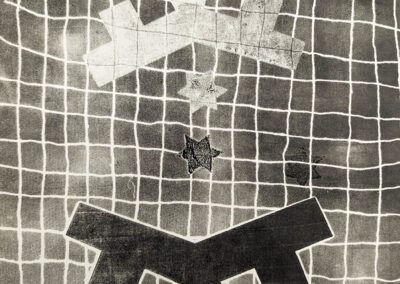

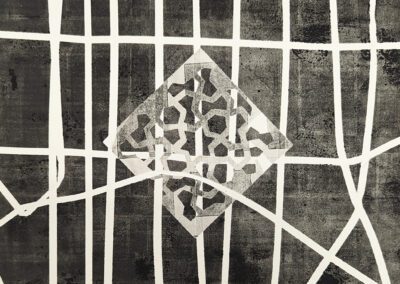

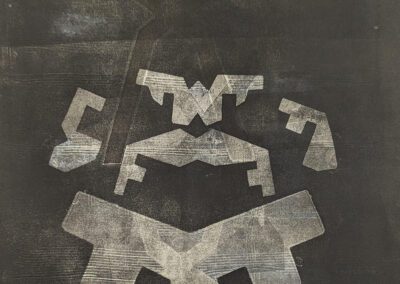

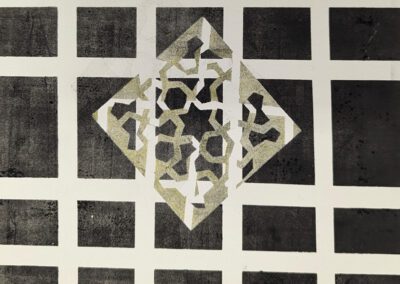

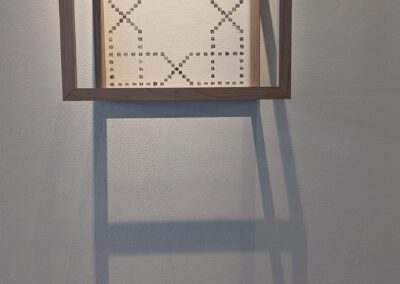

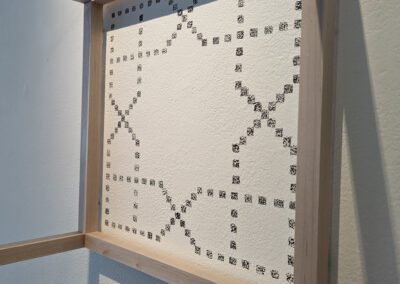

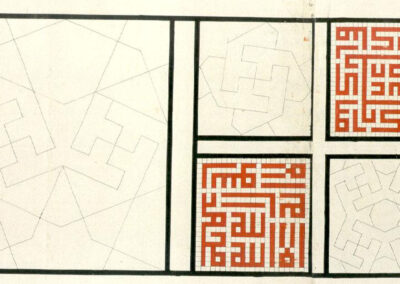

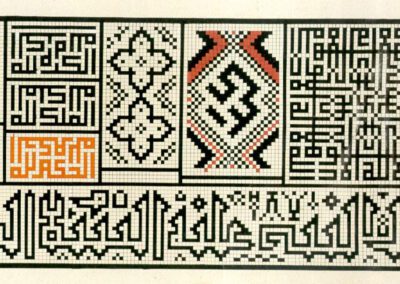

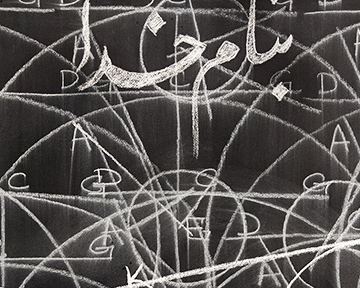

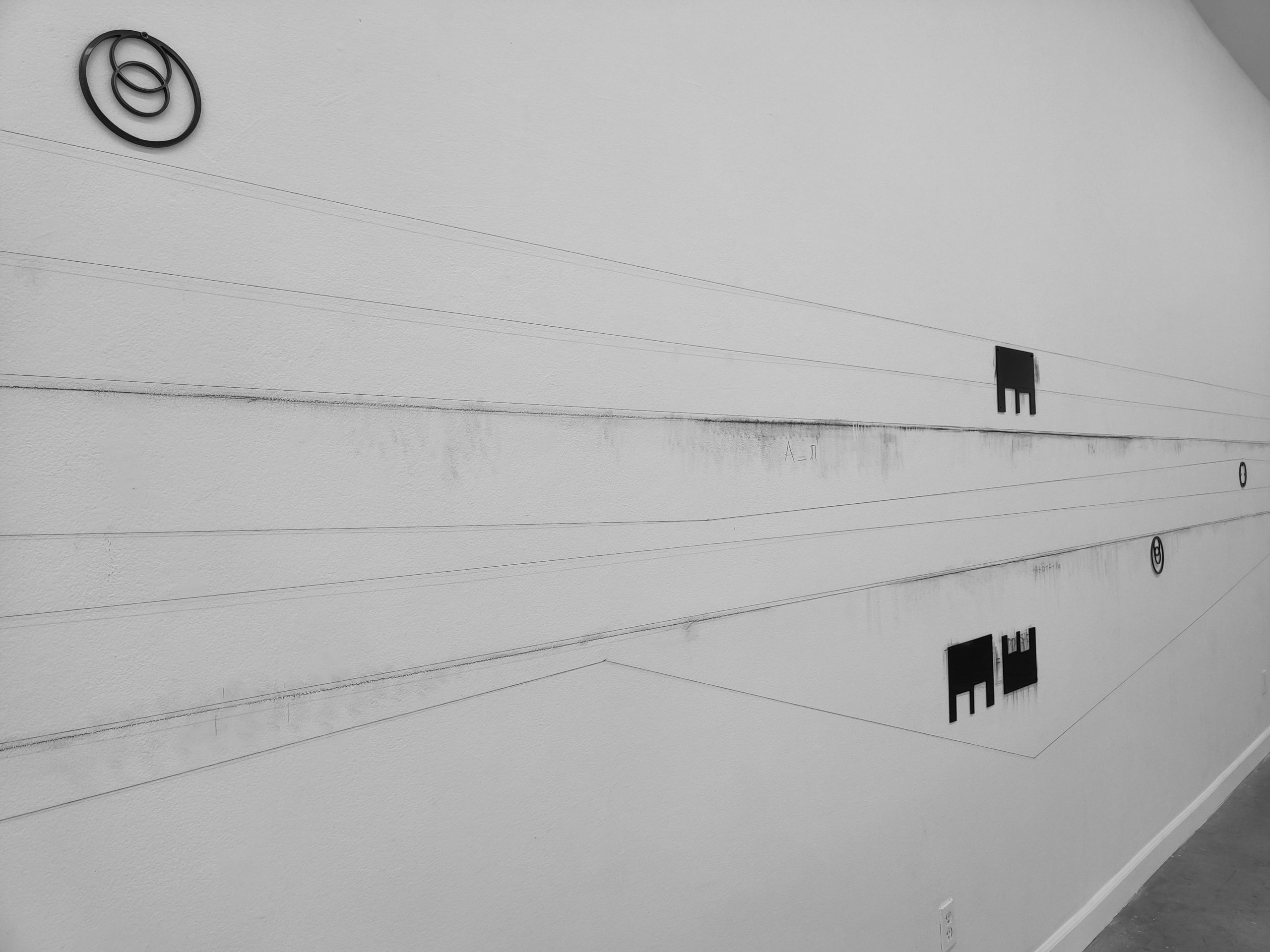

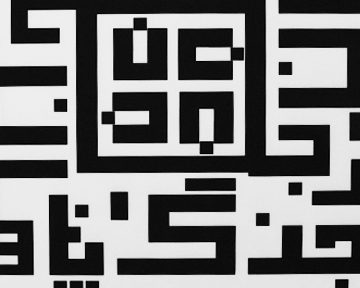

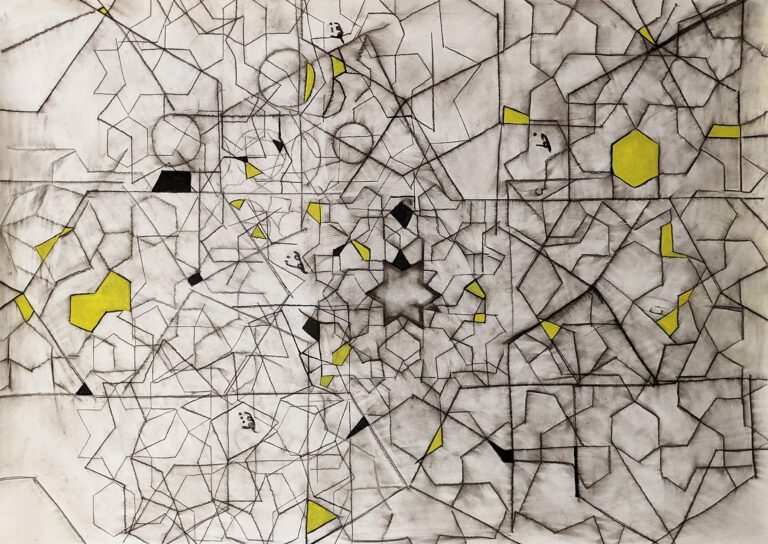

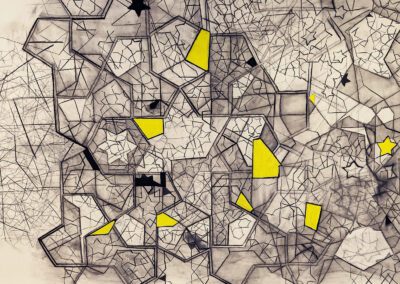

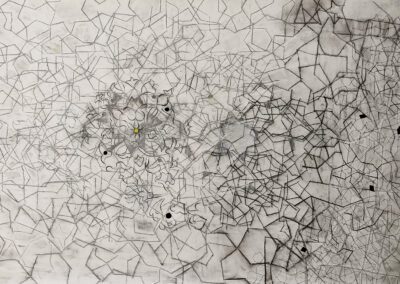

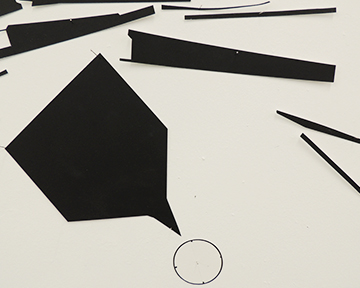

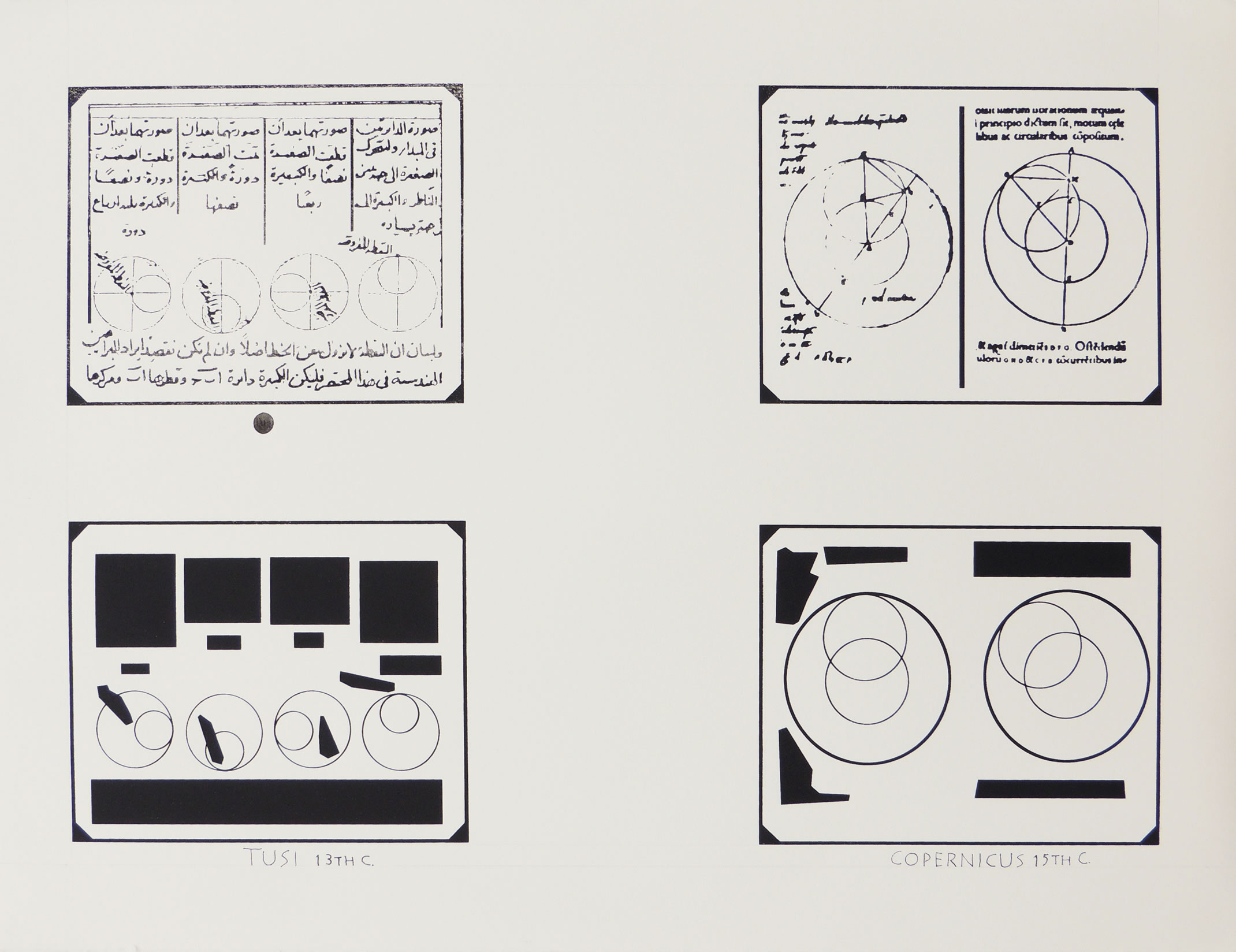

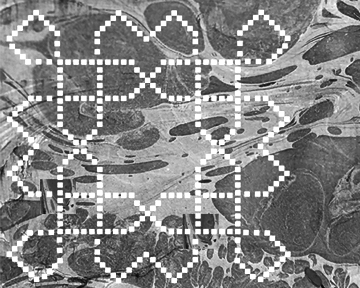

Broken Grid, paper tiles, monotype on paper, 2022

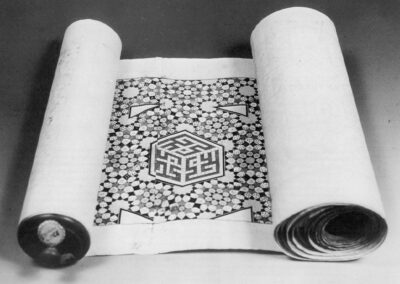

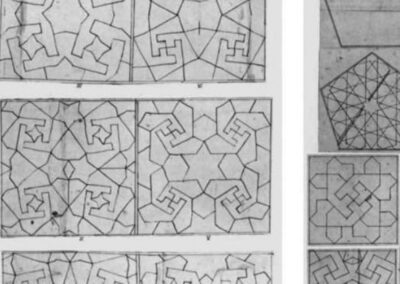

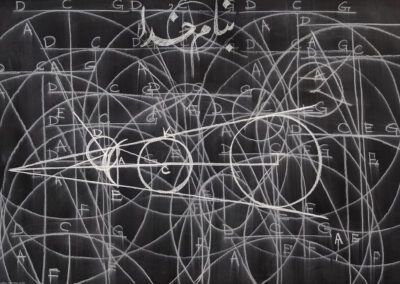

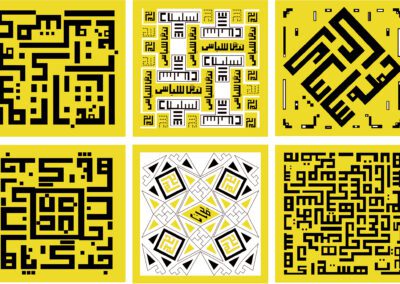

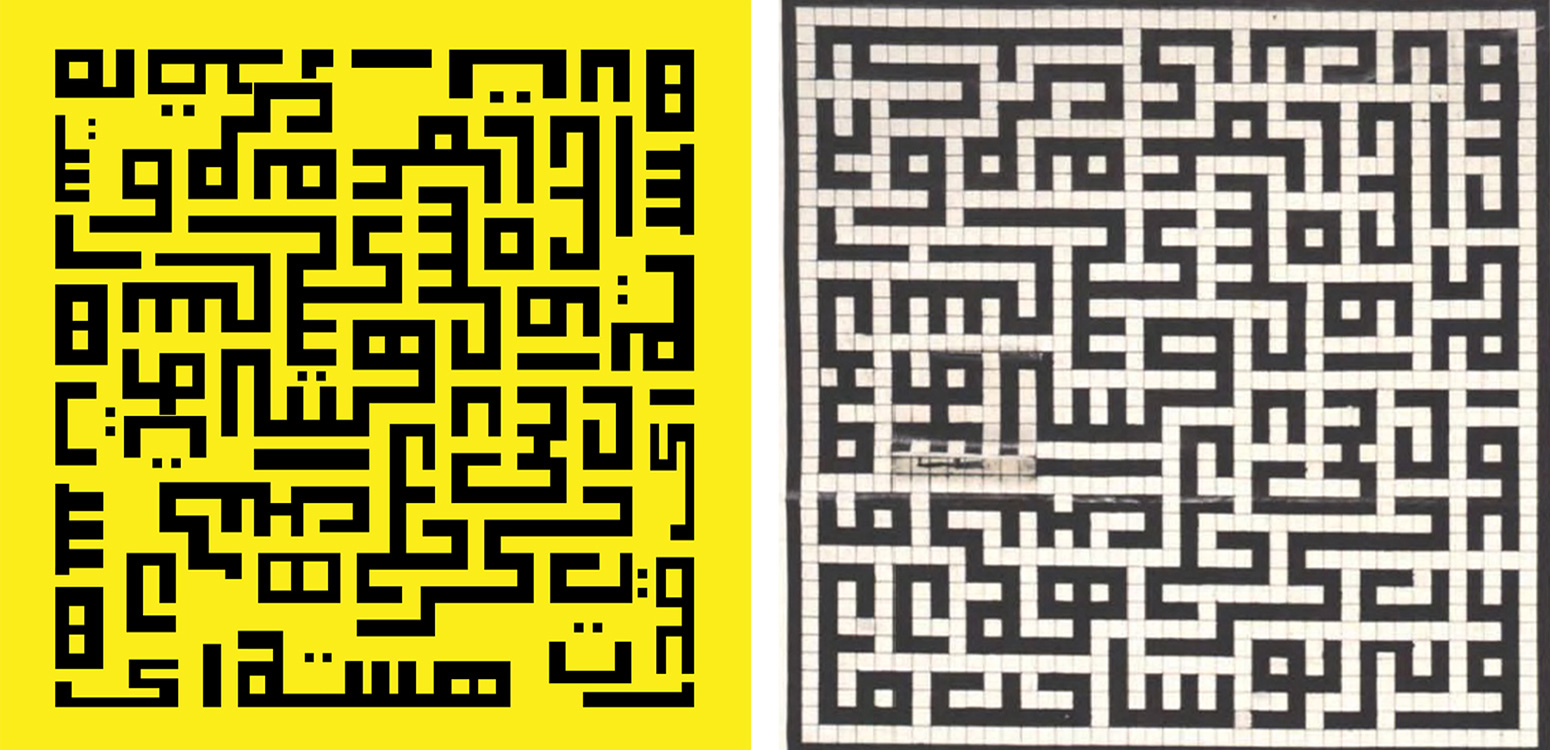

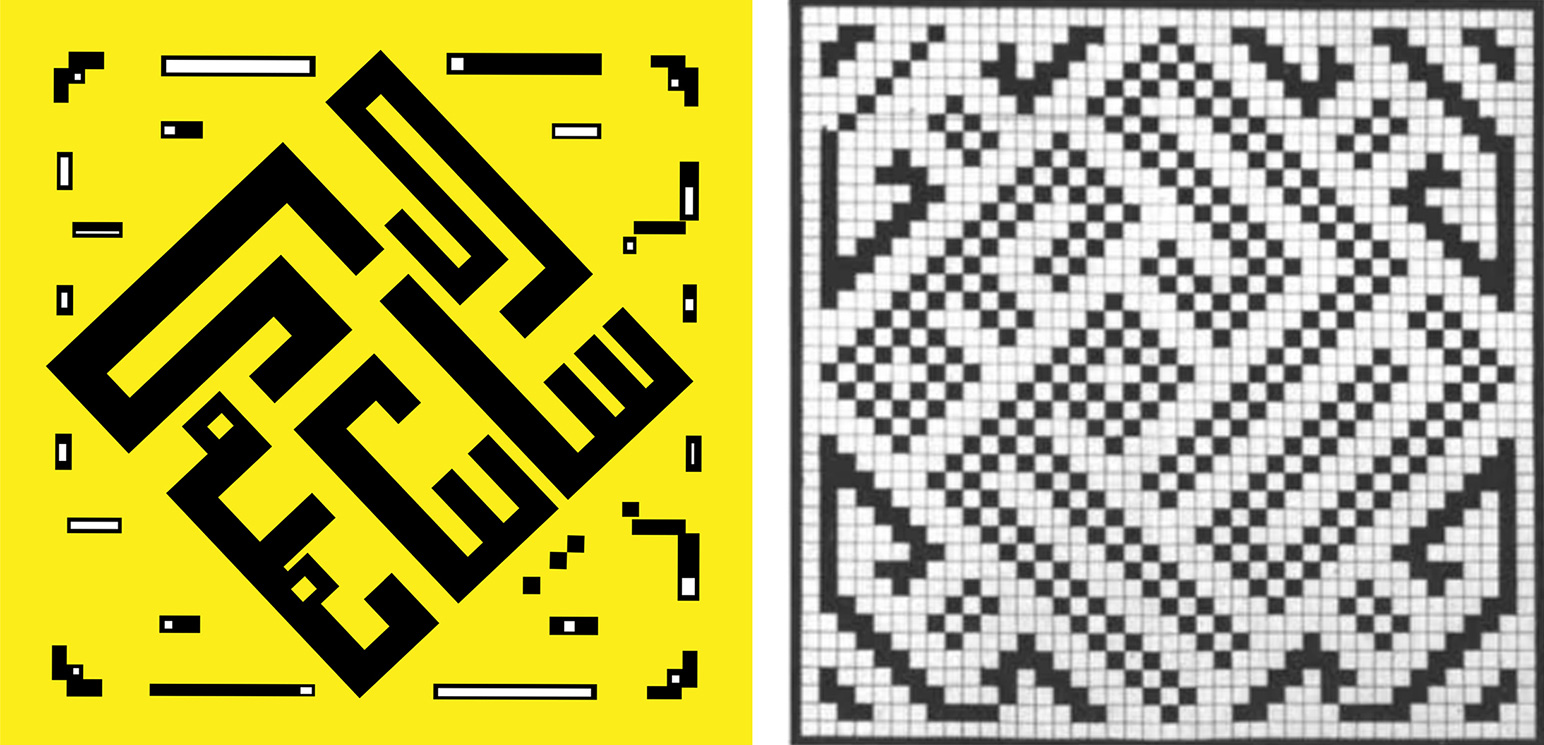

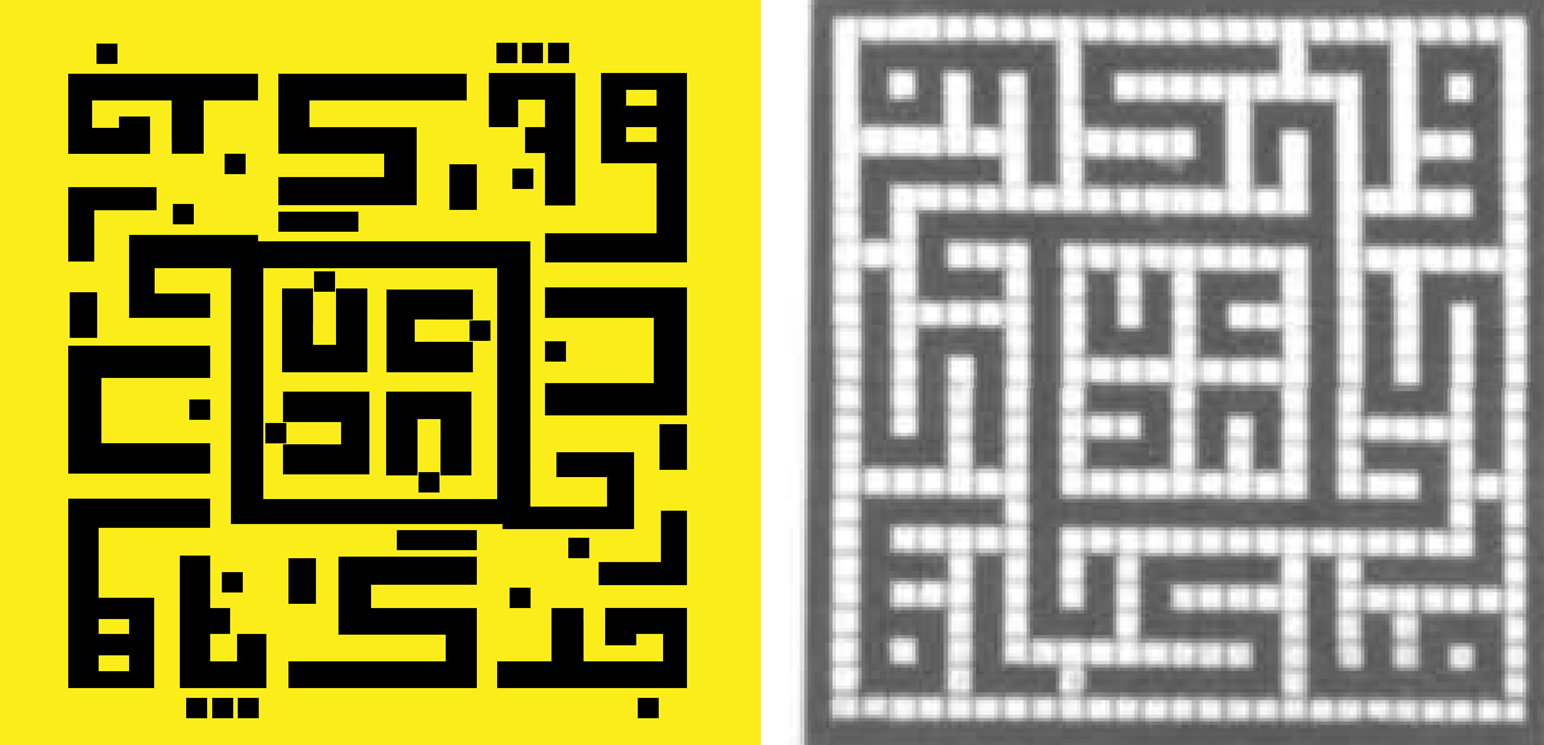

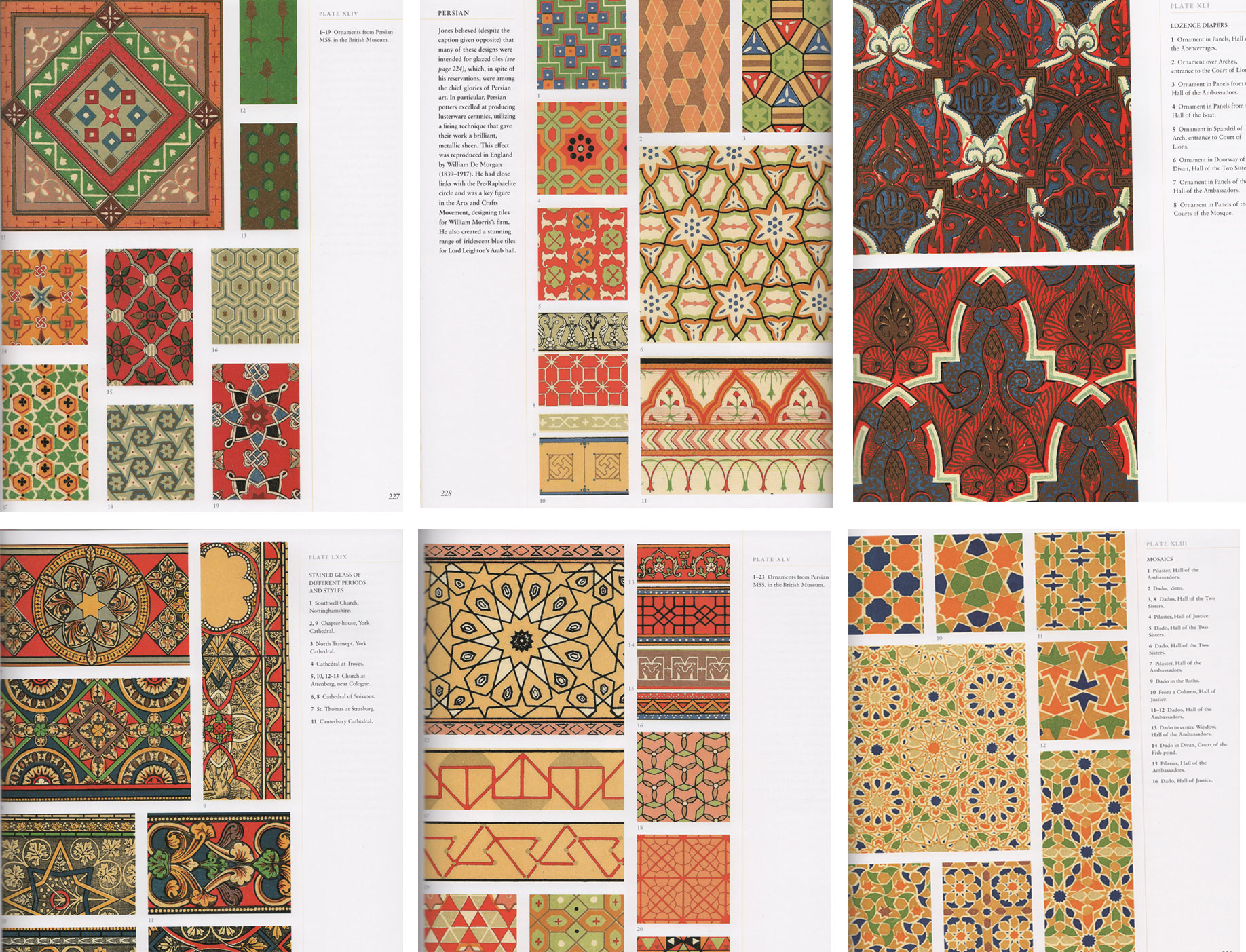

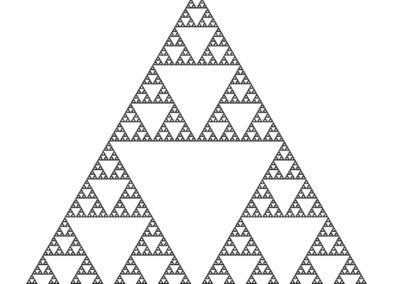

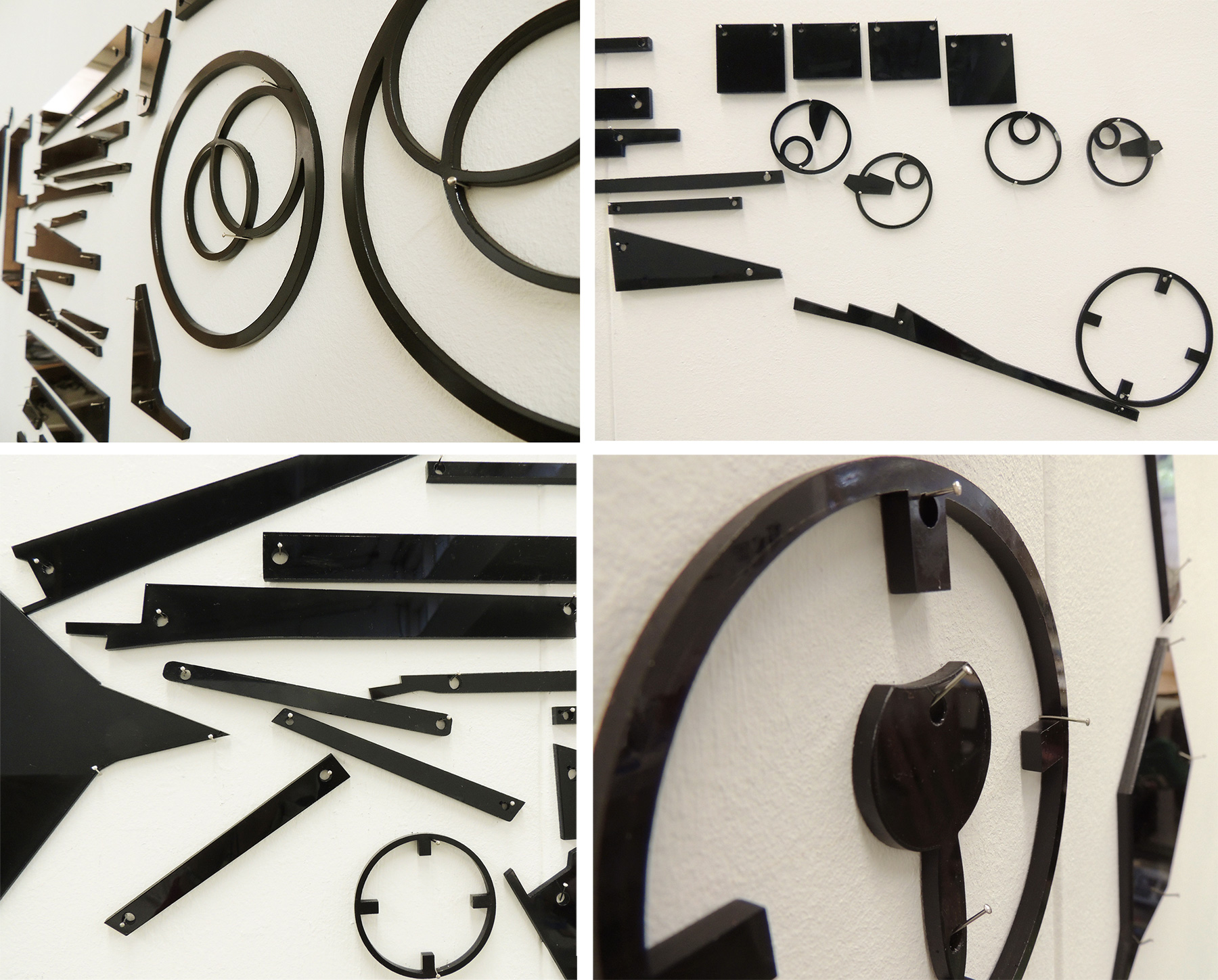

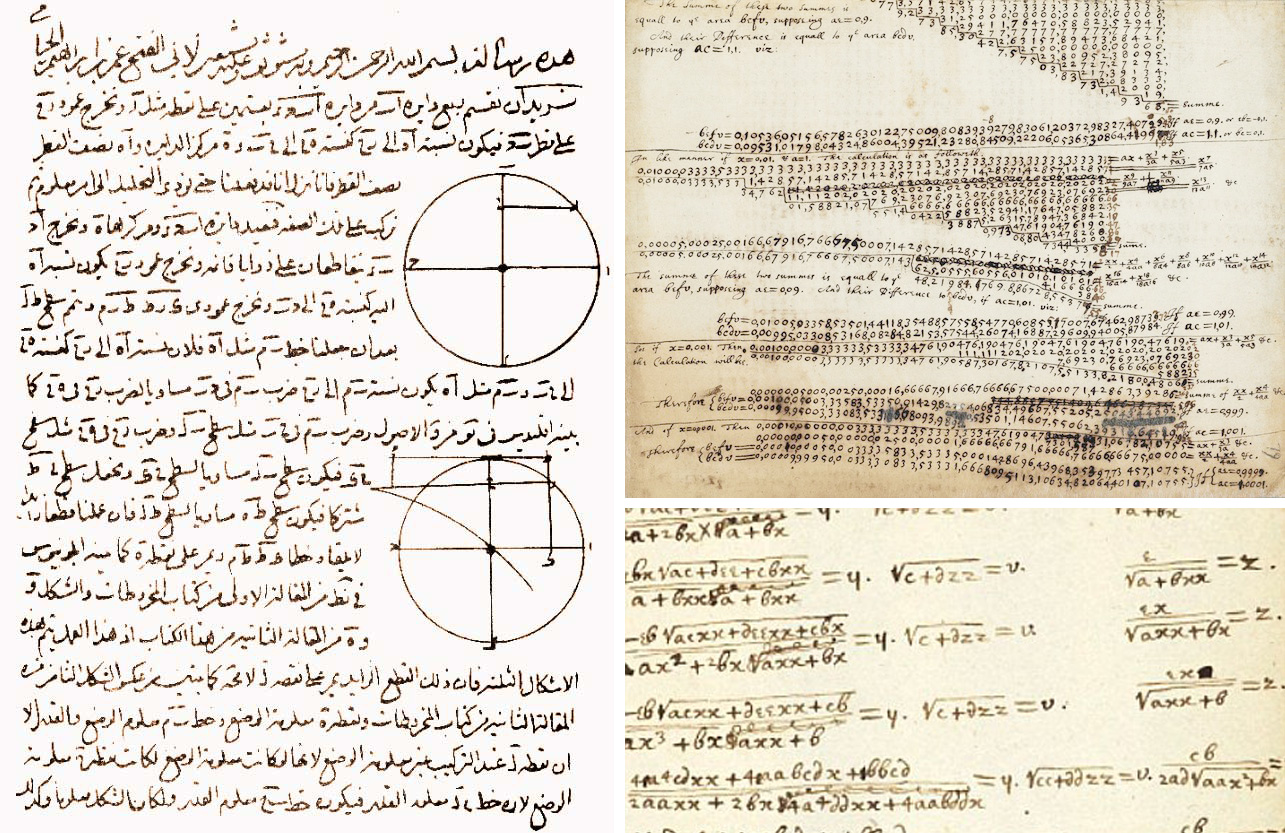

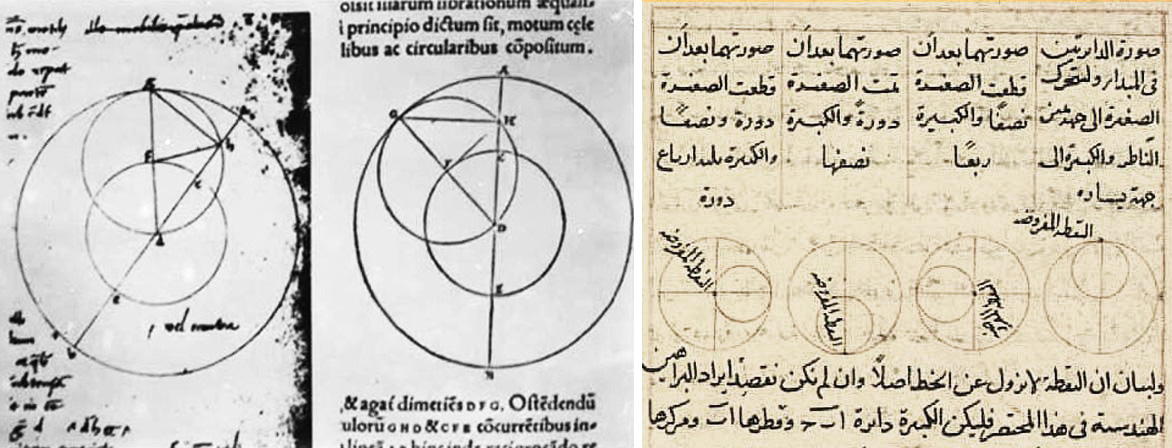

The paper tiles created during my residency at MASS MoCA in May 2022 serve as a profound exploration of my native cultural identity and heritage. Drawing inspiration from the Topkapi scroll, a late medieval Iranian document housed at the Topkapi Palace in Türkiye, these tiles feature geometric designs and Square Kufic script that are deeply rooted in Iranian history and culture.

In my artistic process, I deliberately remove these shapes from their original context and symmetrical arrangements, instead arranging them asymmetrically in distorted grids. Through this artistic intervention, I aim to challenge conventional notions of cultural identity and heritage, inviting viewers to confront the nuances and contradictions inherent in their perceptions. By deconstructing and recontextualizing these traditional motifs, I seek to prompt deeper reflection on the impact of political conflict on cultural memory and how individuals negotiate their identities in the face of adversity.

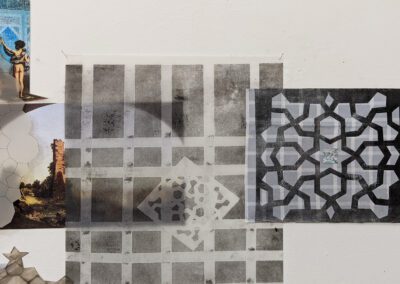

During my residency at MASS MoCA, I further explored these themes by creating a wall installation titled Persian Interiority, American Exteriority. This installation was inspired by my visit to the Olana House in Hudson, NY.

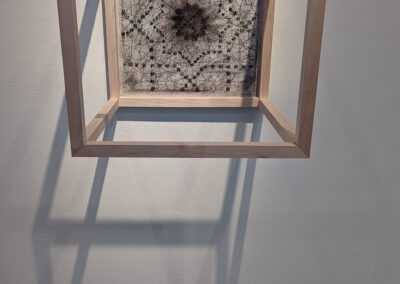

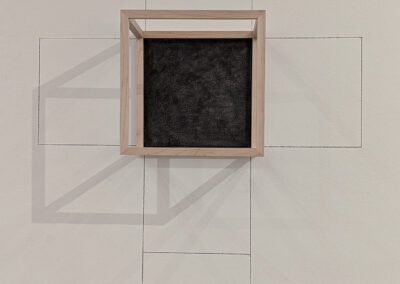

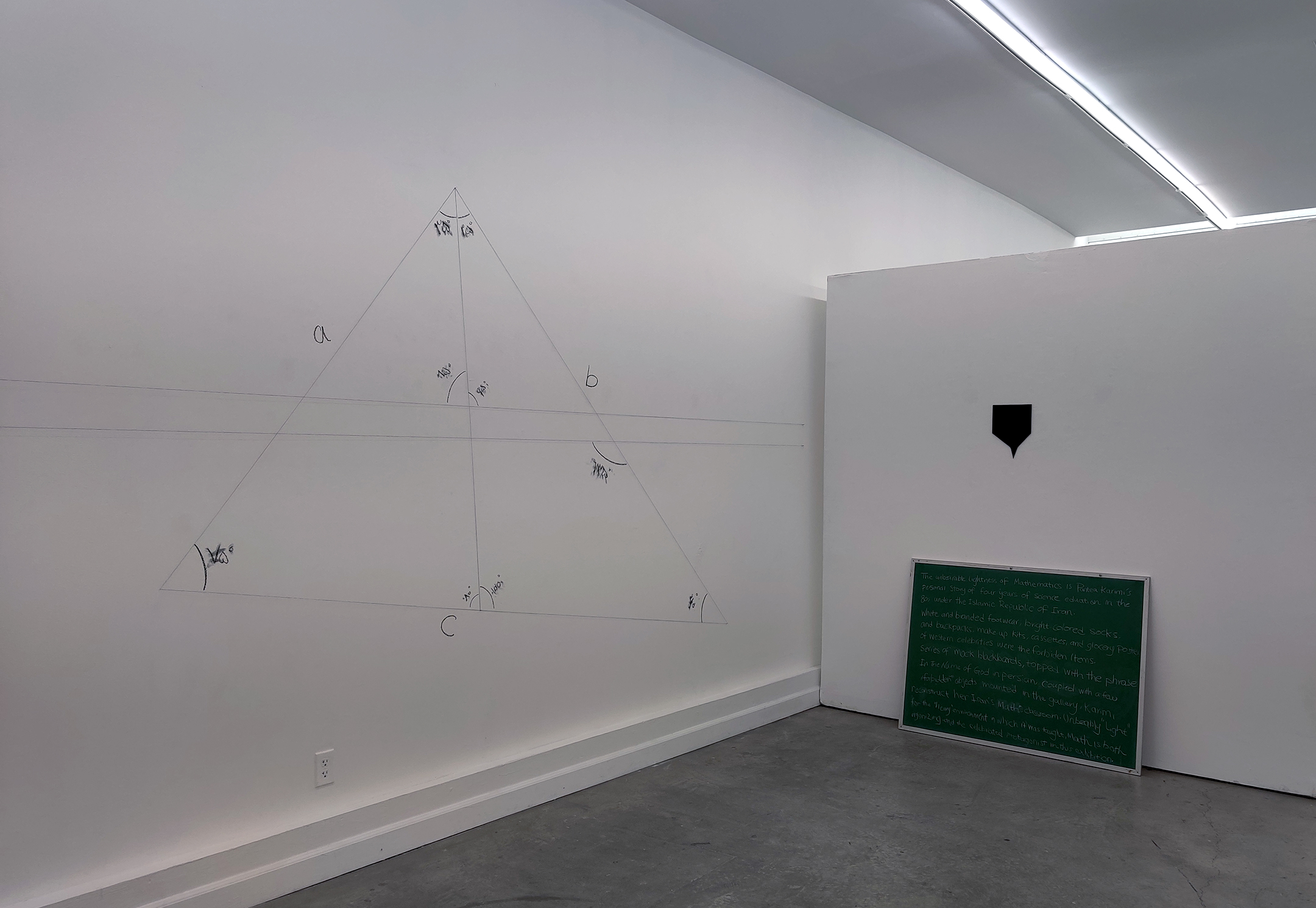

Persian Interiority, American Exteriority, May 2022

Olana House, “Persian Home” of the Hudson River painter Fredrick Church & the Oxbow Painting

In Olana House, which I visited, by framing the colonized landscape through Persian arches and patterns; by blocking “unwanted” views through a seemingly stained-glass Persian window, Church alludes to his desire to take ownership of two inferior civilizations: Olana is the story of a Persian interiority vs. the untamed American exteriority. One is occupied inside and the other is subject to the artist’s colonizer gaze. In the installation, I aim to tackle these Persian interiorities that constantly frame, unframe, reframe, and at times block and obscure the views of the American wilderness using the Persian tile patterns. I’ll do so through a diagrammatic structure installed in a room that reads from left to right, a story similar to that of the Oxbow.

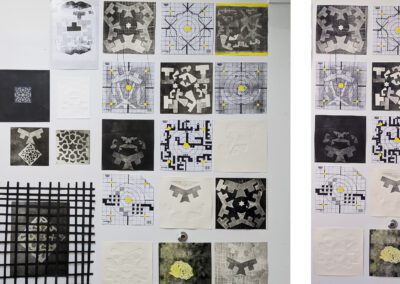

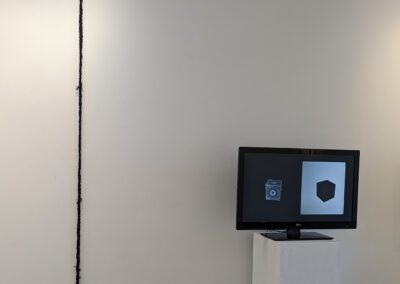

Context Lost, stop motion animation, 2023

Short version (1: 20 seconds), long version (15 minutes).

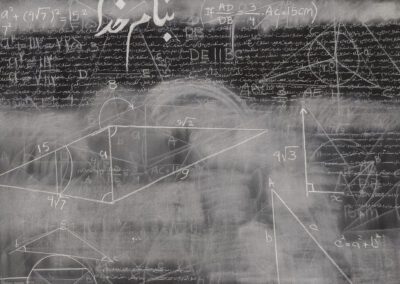

My animation is an exploration of the impact of political conflict on Iran’s rich history of scientific, artistic, and cultural achievement. Drawing inspiration from medieval Iranian tile designs found in the Topkapi scroll document, I employ digitized hand-made marbling prints and geometric forms to create a mesmerizing visual narrative.

In the animation, the digitized marbling prints and geometric forms serve as pixels, gradually fading away until only one pixel remains. This gradual fading process symbolizes the gradual loss of context and meaning caused by political conflict, effectively concealing Iran’s deep history layer by layer.

By introducing questions about the impact of political conflict on Iran’s cultural heritage, I prompt viewers to contemplate the consequences of such conflicts on the preservation and understanding of history. The animation serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of cultural heritage in the face of geopolitical turmoil and the importance of acknowledging and preserving the rich cultural legacy of nations like Iran.

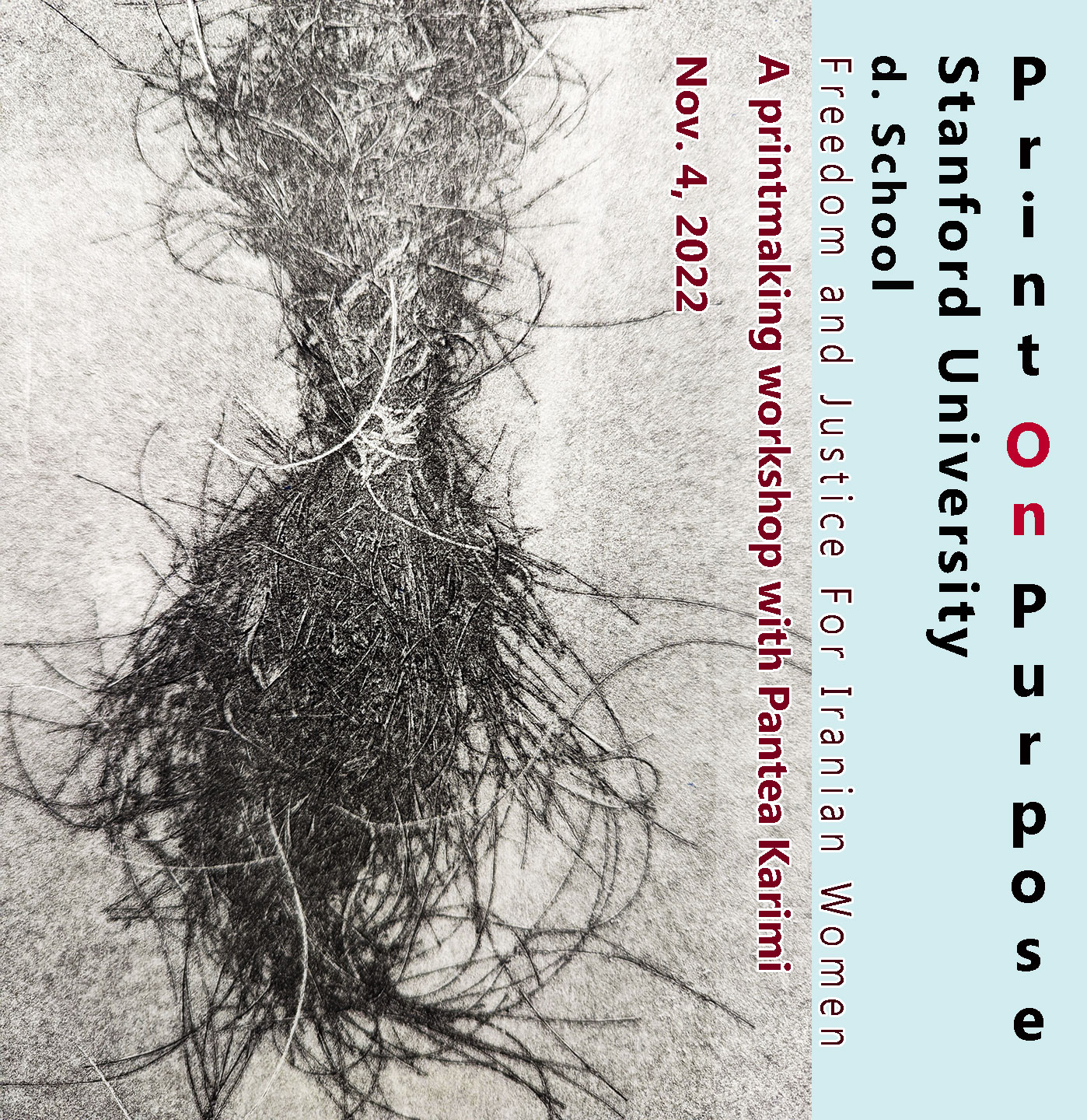

Pantea Karimi’s interview at the Harker Patil Theater at Rothschild Performing Arts Center in November 2023 for the Harker Speaker Series.

Art and Science in Historic and Political Contexts with Pantea Karimi

Interview by Jusha Martinez, Chair of Visual Art at Harker Upper School

Karimi shares insights into her art process, research, and collaborative projects with Harker school students.

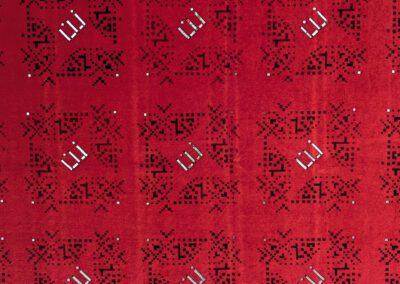

Pixel-Star

Harker School Teaching Residency, 2023

Pantea Karimi worked with 100 students at Harkers, Grades K through 12. Students produced their tile design, creating pixel stars, inspired by medieval Square Kufic methods from Iran.

Research

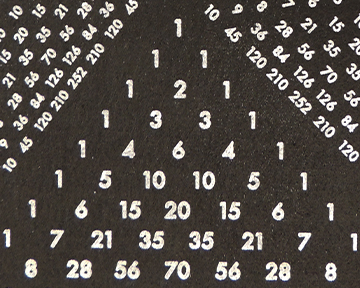

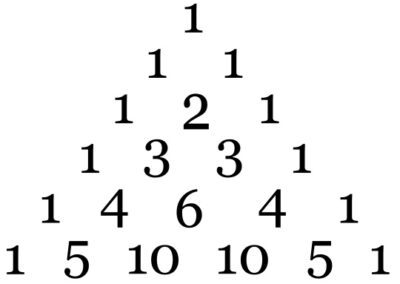

Images from the Topkapi scroll include geometric shapes for tile designs. Images of the historic medieval buildings that used similar Square Kufic tile designs are found in the Topkapi scroll on their facade. An image of the blocked view of the Hudson River landscape by Persian decorative patterns on the window. From Olana House in Hudson, NY, which I took in May 2022. I used them as sources of inspiration for the Context Lost series.