“Saint Saffron” and Pantea Karimi’s Artistic Homage to the Queen of Spices I Spring 2024 I Iranian Diaspora Spotlight I Article

by Dr. Persis Karim,

Director of the Center For Iranian Diaspora Studies

“Saffron is a symbol of the contemporary economic and agricultural challenges that have been convoluted with ongoing political issues under the theocracy in Iran.”

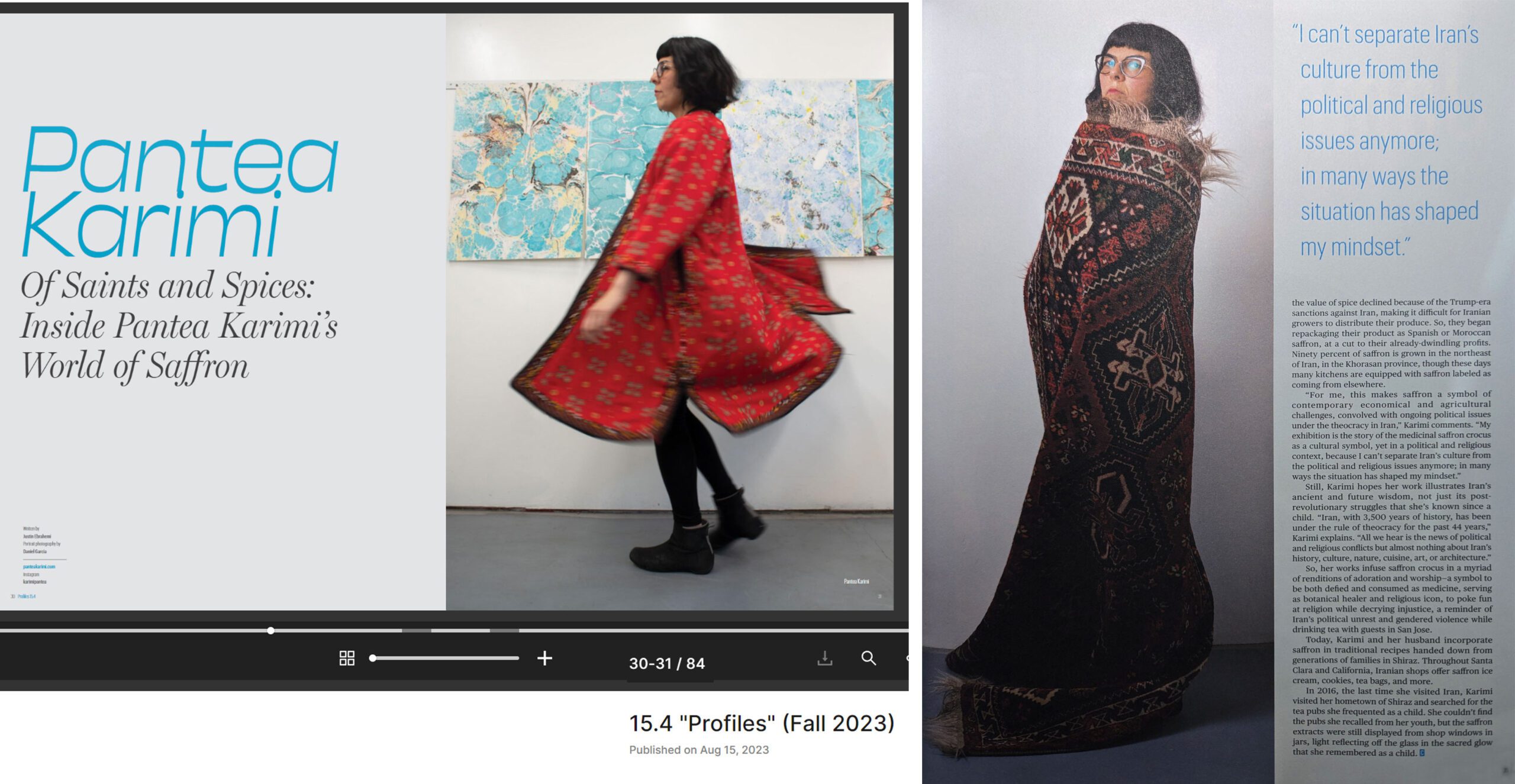

California-based visual artist Pantea Karimi has long been fascinated with the intersection between art and science. Her work spans more than a decade of exploration of the great scientific minds of the medieval Islamic period from Iran and throughout the Muslim world, in prints, installations, sculptures, and other visual media. But nothing has caught her attention quite like the saffron crocus. Her most recent work, Saffron, Saint of Spices now part of a show at the Euphrat Museum of Art at De Anza College in Cupertino, California, pays homage to the role of saffron, its properties and mystical beauty, as well as the ways that the saffron industry in Iran has built on the labor of women. Karimi’s interest in saffron, and more generally in plants and herbs, grows out of her childhood in the famously poetic city of Shiraz, in southern Iran, where she spent countless hours with her family walking and picnicking in Shiraz’s beautiful gardens, especially the famous historic Eram Garden that is located on the Khoshk River.

“I loved all the beautiful plants preserved in this garden, but I was also intrigued by plants and herbs because my grandmother was an herbalist and had knowledge of and prepared many herbal remedies for our family,” she says. In addition to the plants and the elaborate landscaping of the Eram Garden, Karimi says that the geometric and highly mathematical nature of the historic gardens influenced her attraction to the ways that science, math, and philosophy, undergird much of the art produced in the medieval period. Because her father is a retired architect and mathematician, she says she had a natural curiosity for the ways that art and science have been organically intertwined in Iranian arts and “embedded into the psyche” of Iranians over many centuries. It was these early childhood memories, and the influence of her parents and grandmother, that eventually led her to want to explore the role of plants and herbs in the culture, cuisine, and medicine of Iran. During the summer of 2021, she applied for and received a one-year residency at the University of California, San Francisco Library (largely a medical school and scientific research campus of the UC system) where she plunged into a year-long research project reading and studying UCSF’s Library botanical archives.

“My attention was on illustrated books, of which many had been produced at the height of the late medieval and early modern periods. They contained volumes of information, beautiful illustrations, as well as explanations of the properties and uses of many of these plants for medical purposes,” she says. Karimi was particularly interested in some of the earliest manuscripts contained in the USCF Library archives that mention the saffron crocus, the flower from which the saffron spice is derived. The books she found in the archives contained many illustrations, and what she noticed, in particular, was the emphasis on the “artistic” interpretation of saffron, which seemed to depart from the more scientifically oriented explanations of other plants and herbs.

“What I learned is that beyond the beautiful color, the exquisite aroma of this spice, and its pervasiveness in much of the cuisine of the Persianate world, saffron was used as an anti-depressant, as well as in reducing anxiety and improving cognitive abilities,” says Karimi. “I found this fascinating because I knew saffron as the spice that permeated our Iranian cuisine—used in tea, and savory and sweet dishes, but also cherished for its color, but to learn about its importance in medicine made me feel I had something to add as an artist, and especially as an Iranian-born one. After my residency, I thought of paying homage to the saffron crocus through a series of 2- and 3-dimensional pieces that resulted in a solo exhibit at the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Clara, California, in early 2023.” This year, Karimi’s work traveled to Sacred Terrain, a botanical exhibition, at the Euphrat Museum of Art, displayed in a temple-like space that is painted gold. Several of her pieces illustrate the “saintliness” of saffron by drawing on its miraculous and medicinal qualities, by showing how this unique purple flower which blooms for a very short period in the autumn has multiple uses, such as culinary, cosmetics and medicinal. “By drawing attention to the flower’s beauty and its miraculous qualities, I decided to bring its 16th-century depiction into a contemporary context,” says Karimi. One of the pieces in the exhibit is a life-size saffron crocus sculpture after a 16th-century image of the flower that she produced in collaboration with the UCSF Library Makers Lab in 2022 during her residency. Other pieces in the exhibit are made after historic religious objects such as triptychs, shrines and Saqqaakhanaa – the (religious) water fountain. Traditionally visitors would leave votive items like flags or locks on the grided exterior of the Saqqaakhanaa. On one of the shrine sculptures, “Sacred Threads,” Karimi has hand-tied four hundred and fifty votive red threads. They are symbols for healing wishes and the four hundred and fifty saffron threads that make up the 1-gram saffron spice. The illuminated 3-D saffron crocus flower sculpture is shown on this object as a “saint.” The other object in the show is a triptych titled: “A Divine Allegory,” which is inspired by the 18th-century Muslim triptych, hilya-i-sherif. Karimi replicated the design but replaced the botanical vegetation, and the religious texts with saffron crocus archival images and its healing properties, described in the Persian script.

Read full article On With a Trace: Documenting and Sharing the Experiences of the Iranian Diaspora